Table of Contents

Background

The Philippines is an island country in Southeast Asia in the western Pacific Ocean. It is an archipelago that is composed of over 7,000 islands and islets lying about 500 miles off the coast of Vietnam. Its capital city is Manila, which is located on Luzon, the largest island in the country. The name of the Philippines was taken from Philip II, who was king of Spain during the Spanish colonization of the islands back in the 16th century. Since the Philippines was under Spanish rule for 333 years and under US tutelage for 48 years, it has a lot of cultural affinities with the West.

Philippine election illustration

American and Philippine flags

Magellan’s Cross in Cebu, Philippines

Spanish influence preserved in a popular tourism destination up north in the Philippines

It is the second-most-populous Asian country next to India, with English as an official language and one of only two mostly Roman Catholic nations in Asia. Despite the fame of such Anglo-European cultural characteristics, the people of the Philippines are Asian in aspiration and consciousness. [1] If you want to learn more about it, you’re in the right place. In this post, we are giving you the historical timeline of the Philippines, which includes all of the important events that occurred that transformed it into the country we know today.

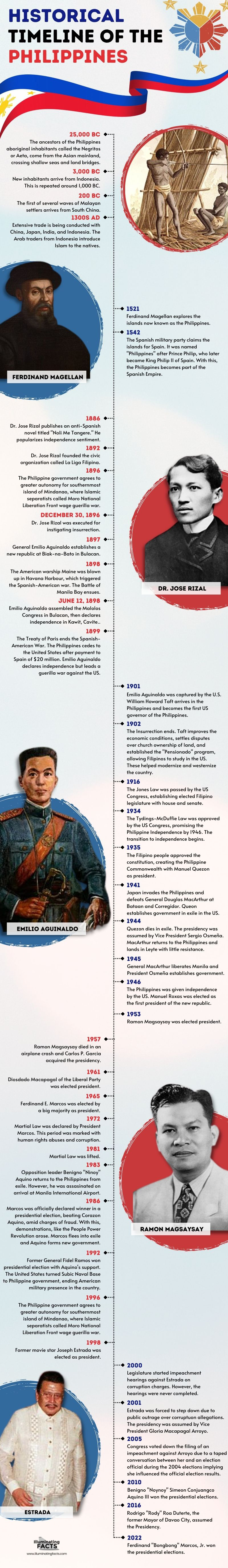

Historical Timeline of the Philippines

Take a look at the infographic below to see the chronological order of the important events that occurred in the history of the Philippines:

Early History of the Philippines

Based on archeological evidence, the Negritos, a broad term for indigenous people of dark complexions, reached the Philippines around 25,000 years ago through a land bridge from the Asian mainland. From 3,000 BC, waves of Indonesians followed, and Malays got a firm foothold around 200 BC. These were followed in later centuries by waves of Chinese settlers. Most Filipinos today have grown out of intermarriages between indigenous and Malay people. The Malays heavily influenced modern Filipino culture, including cuisine and language. They also introduced arts, literature, and a system of government. [2]

A few centuries before the Spanish reached the Philippines in the 16th century, Filipinos were involved in trade and had also met Arabs and Hindus from India, while the expanding Chinese population wielded considerable commercial power. In the late 14th century, Islam entered the Philippines via Borneo. [2]

The first Europeans to arrive in the Philippines were those in the Spanish expedition around the world, led by the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan in 1521. After this, other Spanish expeditions followed, which included one from New Spain (Mexico) under Lopez de Villalobos. In 1542, he named the islands for the infante Philip, later Philip II, the king of Spain. [3]

The Spanish Colonial Era

As mentioned earlier, Ferdinand Magellan was the first European documented to have landed in the Philippines. He arrived in March 1521 during his circumvention of the globe. He claimed the land for the king of Spain, but he was killed by a local chief. After several more Spanish expeditions, the first permanent settlement was established in Cebu in 1565. In 1571, after defeating a local Muslim ruler, the Spanish set up their capital in Manila, and they called their new colony Philippines after King Philip II of Spain.

The Spanish pursued to acquire a share in the profitable spice trade, develop better contacts with Japan and China, and gain converts to Christianity. However, only the third goal was eventually grasped. Like with other Spanish colonies, church and state became inseparably connected in implementing Spanish objectives.

Numerous Roman Catholic religious orders were given the accountability of Christianizing the local population. The civil administration built upon the old village organization and utilized traditional local leaders to rule indirectly for Spain. Through these exertions, a new cultural community was developed. However, Muslims or known as Moros by the Spanish, along with upland tribal peoples, remained detached and alienated. [4]

In 1589, the Spanish governor made a viceroy ruled with the advice of the powerful royal Audiencia. There were frequent uprisings by the Filipinos, who resented the encomienda system, which intended to encourage conquest and colonization. By the end of the 16th century, Manila had become a leading commercial center of East Asia. It supplied some wealth, including gold, to Spain. The period from 1600 to 1663 was marked by continuous wars with the Dutch, who were laying the foundations of their rich empire in the East Indies along with Moro pirates. [3]

From 1756 to 1763, during the Seven Years’ War, Manila was captured by the British East India Company forces. Even though the Philippines was returned to Spain at the end of the war, the British occupation marked the start of the end of the old order. Rebellions broke out in the north, and Moros raided from the south while the Spanish were busy fighting the British.

The renewal of Spanish rule brought reforms meant to promote the economic development of the islands and made them independent of funding from New Spain. In 1815, the galleon trade stopped, and from that date onward, the Royal Company of the Philippines, which was chartered in 1758, promoted direct and tariff-free trade between the islands and Spain. Cash crops were cultivated for trade with Latin America and Europe. However, profits diminished after the Latin American colonies of Spain became independent in the 1810s and 1820s. The Royal Company of the Philippines was eradicated in 1834, and free trade was formally recognized. [4]

The Rise of Nationalism

In the late 19th century, Chinese immigration became a feature in Filipino social and economic life, along with the increasing Filipino native elite class of ilustrados, who became more and more interested in liberal and democratic ideas. However, traditional Catholic priests continued to dominate the Spanish establishment. They resisted the presence of native clergy and were economically secure with their large land holdings and power over churches, schools, and other establishments.

Even though there was prejudice against native priests, brothers, and nuns, some members of Filipino religious orders became famous to the point of leading local religious movements and even rebellions against the establishment. In addition, the ilustrados who returned from education and exile abroad brought new ideas that combined with traditional religion to spur national resistance. [4]

Jose Rizal was among the early nationalist leaders. He was a physician, scientist, writer, and scholar. His writings as a fellow of the Propaganda Movement, which included knowledgeably active, upper-class Filipino activists, had a significant effect on the awakening of Filipino national awareness. With this, his books were banned, and he lived in self-imposed exile.

In 1892, Jose Rizal returned from abroad and founded the La Liga Filipina or Filipino League. It was a national, non-violent political association. However, he was detained after that, and the league was dissolved. One result of this was the division of the nationalist movement between the reform-minded ilustrados and a more radical and independence-minded working-class community. Many of the latter joined the Katipunan, which was a secret society founded in 1892 by Andres Bonifacio that was committed to winning national independence.

In 1896, the Katipunan rose in revolt against Spain. During this time, it had 30,000 members. However, Rizal, who had returned again to the Philippines, was not a member of this society. Due to his alleged role in the rebellion, he was arrested and executed on December 30, 1896. With the martyrdom of Rizal, the rebels led by Emilio Aguinaldo as president became determined. The insurgents were defeated by Spanish troops. However, in December 1897, Aguinaldo and his government went into exile in Hong Kong. [4]

In April 1898, the Spanish-American War broke out, and the fleet of Spain was easily defeated at Manila. Emilio Aguinaldo returned to the Philippines along with his 12,000 troops, who kept the Spanish forces bottled up in Manila until the US troops arrived. Fighting between the American and Filipino troops broke out as soon as the Spanish were defeated.

On June 12, 1898, Emilio Aguinaldo issued a declaration of independence. However, on December 10, 1898, the Treaty of Paris was signed by the United States and Spain, which ceded the Philippines along with Guam and Puerto Rico to the United States. Cuban independence was also recognized, and $20 million was given to Spain.

On January 21, 1899, a revolutionary congress assembled at Malolos, north of Manila, propagated a constitution, and inducted Aguinaldo as president of the new republic after two days. In February 1899, conflicts broke out, and by March 1901, Aguinaldo was seized, and his forces were defeated. Even though Aguinaldo called on his fellow citizens to lay down their arms, rebellious resistance was still sustained until 1903. Doubtful of both the Christian Filipino insurgents and the Americans, the Moros remained mostly neutral. However, their own armed resistance ultimately had to be subjugated. Moro territory was placed under the United States military control until 1914. [4]

The American Era

The first phase of the rule of the United States over the Philippines was from 1898 to 1935. Washington well-defined its colonial mission as one of teaching and preparing the Philippines for eventual independence. During these times, political administrations were quickly established. The Philippine Assembly, or lower house, and the United States-appointed Philippine Commission, or upper house, served as a bicameral legislature.

The ilustrados created the Federalista Party. However, their statehood platform had limited appeal. The party was then renamed in 1905 as the National Progressive Party, and it took up a platform of independence. In 1907, the Nacionalista Party was formed, and it dominated Filipino politics until after World War II. The leaders of this party were not ilustrados, and even with their immediate independence platform, they participated in collaborative leadership with the United States.

The second phase of the United States’ rule over the Philippines occurred from 1936 to 1946. This period was characterized by the establishment of the Commonwealth of the Philippines and occupation by Japan during World War II. In 1934, legislation was passed by the US Congress, which provided for a 10-year period of transition to independence. In 1934, the first constitution of the country was outlined and overpoweringly accepted by referendum the following year. After that, Manuel Quezon was elected president of the Commonwealth.

In 1944, Quezon died in exile and was succeeded by Vice President Sergio Osmeña. On December 8, 1941, the Philippines was attacked by the Japanese. Manila was occupied by Japan on January 2, 1942. After this, Tokyo set up an ostensibly independent republic, which was opposed by underground and guerilla activity. One of the major elements of the resistance in the Central Luzon area was furnished by the Hukbalahap or People’s Anti-Japanese Army. The Philippines was invaded by allied forces in October 1944. On September 2, 1945, the Japanese surrendered. [4]

Early Independence Era

The Philippines agonized from widespread inflation and shortages of food and other goods during World War II. Different trade and security issues with the United States also continued to be settled before Independence Day. The Allied leaders wanted to eliminate the officials who collaborated with the Japanese during the war and deny them the right to vote in the first postwar elections. But Commonwealth president Osmeña countered that each case should be tried on its own merits.

On July 4, 1946, independence from the United States came, and Manuel Roxas was avowed in as the first president. In March 1947, a bilateral treaty was signed, by which the US continued to give military aid and training. This was judicious as the Hukbalahap guerillas rose again. During this time, they were in contradiction with the new government. They reformed their name to the People’s Liberation Army and necessitated the disbandment of the military police, political participation, and a general pardon. However, their negotiations failed, and a rebellion started in 1950 with communist support, which aimed to overthrow the government. By 1951, the Huk movement degenerated into criminal activities as the Philippine armed forces and peacemaking government moved toward the laborers, offsetting the efficiency of the Huks. [4]

In 1953, Ramon Magsaysay of the Nacionalista Party was elected president. He boarded on extensive reorganizations that helped tenant farmers in the Christian north while aggravating conflicts with the Muslim south. The remaining leaders of Huks were captured or killed, and the movement had faded by 1954. In 1957, Ramon Magsaysay died in an airplane crash, and he was succeeded by Vice President Carlos P. Garcia. The same year, Garcia was elected in his own right, and he advanced the nationalist theme of “Filipinos First.”

The Liberal Party candidate Diosdado Macapagal was elected president in 1961. During his presidency, successive discussions with the United States over base rights led to significant anti-American feelings and protests. He sought closer relations with Southeast Asian countries and arranged a conference with the leaders of Indonesia and Malaysia in the expectation of raising a spirit of consensus. However, this did not emerge. [4]

The Marcos Era and Beyond

Ferdinand E. Marcos became the president of the Philippines in 1965 after defeating Macapagal in the elections. He inherited the territorial dispute over Sabah, and in 1968, he approved a congressional bill annexing Sabah to the Philippines. Malaysia suspended diplomatic relations, and the matter was referred to the United Nations.

In 1967, the Philippines became one of the founding countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). The continuous need for land reform fostered a new Huk uprising in Central Luzon, along with mounting assassinations and acts of terror. In 1969, Marcos started a major military campaign to subdue them. In Mindanao, civil war also threatened, where groups of Moros opposed Christian settlement.

Marcos won unparalleled re-election in November 1969, beating Sergio Osmeña, Jr. However, the election was escorted by charges of deception and violence. The second term of Marcos started with increasing civil disorder.

In January 1970, around 2,000 demonstrators attempted to storm the Malacañang Palace, which is the presidential residence. There were also riots that erupted against the United States Embassy. In November 1970, Pope John Paul VI visited Manila, and an attempt was made on his life. In 1971, at a Liberal Party rally, the speakers’ platform was thrown with hand grenades, and several people were killed. In September 1972, President Marcos declared martial law, charging that a Communist rebellion threatened. [3]

In 1973, the 1935 constitution was replaced by a new one, which gave the president direct powers. In July 1973, a referendum gave Marcos the right to continue in office beyond the end of his term. In the meantime, the fighting on Mindanao had spread to the Sulu Archipelago. Some 3,000 villages burned by 1973. Throughout the 1970s, poverty and governmental corruption increased. Imelda Marcos, Ferdinand Marcos’ wife, also became more influential.

Until 1981 when Marcos was re-elected, Martial Law remained in force. On August 21, 1983, opposition leader Benigno Aquino was assassinated at Manila airport. This event provoked a new and more powerful wave of anti-Marcos opposition. After the presidential election in February 1986, both Marcos and Corazon Aquino, the widow of Benigno, acknowledged themselves as the winner. There were charges of huge fraud and violence that were pressed against the Marcos party. The domestic and international support of Marcos eroded. On February 25, 1986, the People Power Revolution occurred. The Marcoses fled the country and eventually obtained asylum in the United States. [3]

Corazon Aquino became the president of the Philippines after Marcos left. Her government faced increasing problems, including substantial economic difficulties, rebellion attempts, and pressure to free the country of the US military presence. In retort to the Moros, in 1990, a partially autonomous Muslim region was established in the far south of the country.

Aquino refused to run for re-election in 1992. She was succeeded by her previous army chief of staff, Fidel Ramos. He launched an economic revival plan focused on three policies, which are government deregulation, political solutions to the continuing revolutions in the country, and increased private investment. His political program was somewhat successful. However, Muslim discontent with partial rule persisted. Throughout the 1990s, unrest and violence continued. [3]

In 1998, a former movie actor, Joseph Estrada, was elected president. He pledged to help the poor and develop the agricultural sector of the country. However, late in 2000, his presidency was battered by charges that he accepted millions of dollars in payoffs from illegal gambling operations. This led businesses, churches, and the majority of people to call for him to resign. He was impeached by the house of representatives on charges of graft in November 2000. The presidency was acquired by Vice President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo.

In May 2004, Gloria Arroyo was elected president in her own right. However, the balloting was marred by violence and irregularities. [3] In 2005, Congress voted down the filing of impeachment against Arroyo due to a taped conversation between her and an election official during the 2004 elections implying she influenced the official election results.

In 2010, Benigno Simeon Cojuangco Aquino III, son of Corazon Aquino, won the presidential elections. In 2016, the presidency was assumed by Rodrigo Roa Duterte, a former Mayor of Davao City. In 2022, Ferdinand Marcos, Jr., son of Ferdinand Marcos, Sr., won the presidential elections.

Conclusion

The Philippines indeed had a long and rich history before it became the country we know today. It may be a small country compared to others, but many historical events have taken place in this land. From being occupied by the Spanish for 333 years to 48 years of American colonization, there are truly a lot of people and events that helped in shaping the culture and traditions of the Philippines. We hope this post helped you learn more about the history of the Philippines.

References

[1] Borlaza, G. C. (2022, July 29). Philippines. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved August 3, 2022, from https://www.britannica.com/place/Philippines

[2] Matthieu. (n.d.). Philippines History and Timeline. Insightguides.com. Retrieved August 3, 2022, from https://www.insightguides.com/destinations/asia-pacific/philippines/historical-highlights

[3] DLSU-Manila, P. E. (2002). Philippine History. Philippine history. Retrieved August 3, 2022, from https://pinas.dlsu.edu.ph/history/history.html

[4] Kästle, K. (n.d.). History of the Philippines. History of Philippines. Retrieved August 3, 2022, from https://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/History/Philippines-history.htm