Background

The Middle Ages are a time in European history that extends from the fall of the Roman Empire in the fifth century CE to the Renaissance, which is variously understood as beginning in the thirteenth, fourteenth, or fifteenth centuries, depending on the location of Europe and other variables. [1] From the fall of Rome in 476 CE to the start of the Renaissance in the 14th century, Europe is claimed to have been in the “Middle Ages.” Instead of using the term “Middle Ages,” many academics prefer to use the term “medieval period,” arguing that it implies the era was merely a passing blip between two much more significant eras. [2]

The Medieval Era was among the most turbulent and transformative periods in history. It was popularized by the Black Death, Magna Carta, and the Hundred Years’ War. If you want to learn more about this period in history, we are here to help you. In this post, we are giving you a timeline of the Medieval Era along with the important events that occurred during those times.

an illustration of a European Medieval town

the Speyer Cathedral in Germany

Mosques and pyramids in Cairo

monument of Charlemagne

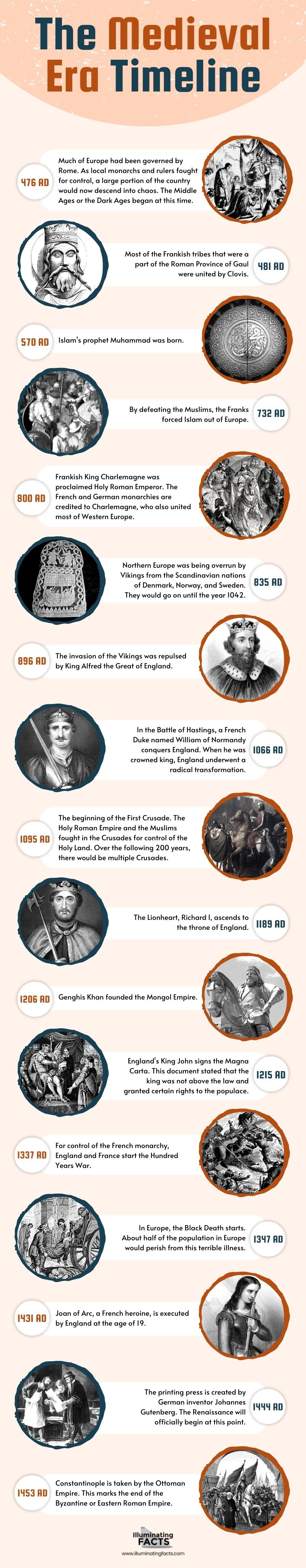

The Medieval Era Timeline

Take a look at the timeline below to see the important dates and events during the Medieval Era:

Terminology

The terms “medieval period” and “medieval era” are derived from the Latin terms medies (middle) and aevus (age), respectively. Early historians have referred to non-European nations as “medieval” when they exhibit “feudal” organizational traits. However, modern historians are much less likely to try to fit the history of other regions to the European model, and these applications of the term outside of Europe have fallen out of favor. The term “medieval” is also sometimes used to describe Japan’s pre-Westernization era and the pre-colonial era in developed sub-Saharan Africa. [3]

The Beginning of the Medieval Era

During the 2nd century, the Roman Empire’s territory expanded to its greatest extent. Roman dominance over its outlying kingdoms gradually waned over the course of the next two centuries. In 285 CE, the eastern and western regions of the empire were divided and independently governed. He arranged for a lesser emperor to rule the western Roman empire from Ravenna, and the area was to be subject to the more affluent east. Constantine, who refounded the city of Byzantium as the new capital, Constantinople, in 330, fostered the split between east and west. [3]

Roman institutions were in disarray by the end of the fifth century. Romulus Augustulus, the last independent, ethnically Roman emperor in the west, was overthrown by the barbarian ruler Odoacer in 476. After the fall of its western counterpart, the Eastern Roman Empire (known as the “Byzantine Empire”) preserved its order by leaving the west to its fate. No barbarian ruler ventured to assume the title of emperor of the west, despite the fact that Byzantine emperors still claimed the region. Hence attempts to restore Byzantine rule over the region failed.

The western empire would be without a genuine emperor for the following three centuries. Instead, it was ruled by kings who had the backing of armies that were mostly composed of barbarians. Some kings held power in their own right, while others served as regents for titular emperors. Cities all around the empire began to fall during the fifth century, retreating behind well-defended walls. Because the central authority did not adequately maintain the infrastructure, the western empire, in particular, underwent degradation. Where public services and infrastructure were maintained like as chariot races, aqueducts, and highways, the cost of the work was typically borne by city leaders and bishops. [3]

The Catholic Church in the Medieval Era

The inhabitants of the European continent were not united by a single state or administration when Rome fell. Instead, the Catholic Church rose to prominence as the most influential organization throughout this time. A significant portion of the authority of kings, queens, and other figures of authority came from their ties to and protection of the Church.[2]

For instance, Pope Leo III designated the Frankish monarch Charlemagne as the “Emperor of the Romans” in 800 CE—the first such designation since the fall of the Roman Empire more than 300 years earlier. Over time, Charlemagne’s domain evolved into the Holy Roman Empire, one of several European political bodies whose objectives frequently coincided with those of the Church.

While the Church was largely exempt from taxation, the average person in Europe was required to “tithe” the Church 10% of their annual income. It accumulated a lot of wealth and influence as a result of these policies.[2]

The Rise of Islam in the Medieval Era

The Islamic world was expanding and becoming more powerful throughout this time. After the death of the prophet Muhammad in 632 CE, Muslim troops occupied a significant portion of the Middle East and brought it under the control of a single caliph. At its largest, the Islamic world in medieval times was more than three times bigger than the entire Christian world.

Great towns like Cairo, Baghdad, and Damascus fostered a thriving intellectual and cultural life under the caliphs. Numerous works were written by scientists, philosophers, and poets. Arabic books were translated from Greek, Iranian, and Indian sources. The pinhole camera, soap, windmills, surgical tools, the early flying machine, and the current system of numerals were all created by inventors. The Quran and other sacred writings were also translated, interpreted, and taught to people throughout the Middle East by religious academics and mystics.[2]

The Medieval Era Crusades

The Catholic Church started to sanction military expeditions, known as Crusades, to drive Muslim “infidels” from the Holy Land around the end of the 11th century. Crusaders thought that their service would assure the forgiveness of their sins and their ability to spend all of eternity in Heaven. They donned red crosses to signify their status and wore them on their jackets. They also obtained more material benefits, such as papal protection for their assets and debt payment relief.

When Pope Urban sent a Christian army to battle its way to Jerusalem in 1095, the Crusades were launched. They lasted intermittently through the end of the 15th century. After Christian soldiers liberated Jerusalem from Muslim rule in 1099, pilgrimage to the Holy Land began to spread throughout Western Europe. However, a large number of them perished when traveling through areas under the control of Muslims.[2]

The Knights Templar was a military organization founded in the year 1118 by a French knight named Hugues de Payens and eight family members and friends. They gained the favor of the pope and a reputation as fierce warriors. The final Crusader sanctuary in the Holy Land was destroyed with the Fall of Acre in 1291, and Pope Clement V expelled the Knights Templar in 1312.

The Crusades were a losing battle for everyone involved, as thousands of individuals on both sides were killed. They did foster a sense of unity among ordinary Catholics throughout Christendom, and they sparked surges of religious fervor among those who may have otherwise felt cut off from the established Church. Additionally, they introduced the Crusaders to Islamic literature, science, and technology—exposure that had a long-lasting impact on the intellectual life of Europe.[2]

The Art and Architecture of the Medieval Era

The construction of opulent cathedrals and other ecclesiastical institutions like monasteries was another way to demonstrate loyalty to the Church. The biggest structures in medieval Europe were cathedrals, which might be found at the heart of any town or city. Most cathedrals in Europe were constructed in the Romanesque architectural style between the 10th and 13th centuries. Romanesque cathedrals are strong and substantial structures with thick stone walls, few windows, rounded masonry arches, and barrel vaults supporting the roof. Romanesque structures include the Speyer Cathedral in present-day Germany and the Porto Cathedral in Portugal.[2]

Around 1200, the Gothic architectural style was adopted by church builders. Gothic structures have large stained-glass windows, pointed vaults and arches (a design innovation from the Islamic world), spires, and flying buttresses, as those found in the Abbey Church of Saint-Denis in France and the newly renovated Canterbury Cathedral in England. Gothic architecture appears to be quite weightless in comparison to the massive Romanesque structures. Other styles of religious art were used throughout the middle ages. Church interiors were ornamented with frescoes, mosaics, and paintings of the Virgin Mary, Jesus, and saints.

Even books were works of art prior to the printing press’s introduction in the 15th century. Illuminated manuscripts are handmade religious and secular texts with colored drawings, gold and silver lettering, and other adornments that were produced by artisans in monasteries (and later in colleges). Nuns also wrote, translated, and embellished manuscripts, making convents one of the only institutions where women could pursue higher education. Urban booksellers started selling smaller illuminated manuscripts, such as psalters, books of hours, and other prayer books, to affluent people in the 12th century.[2]

The Late Medieval Era

Calamities and upheavals set the Late Middle Ages in motion. Climate historians have documented a climate change that had an impact on agriculture during this time and caused recurrent famines in the area, most notably the Great Famine of 1315–1317.

The Black Death, a bacterial epidemic brought into Europe via the Silk Road from Southeast Asia and spread like wildfire among the malnourished populace, killed up to a third of the population by the middle of the fourteenth century; in certain areas, the death toll was as high as one half. The dense population made towns particularly hard-hit. Large swaths of land remained uninhabited, and some fields remained untended. [3]

Due to the unexpected decrease of employees available, wages increased as landlords tried to lure workers to their fields. Additionally, workers believed they had a right to higher pay, which led to widespread upheavals across Europe. Contrarily, during this time of stress, there were innovative social, economic, and technological reactions that prepared the way for even more significant transformations throughout the Early Modern Period.

The Catholic Church was likewise becoming more and more divided against itself during this time. As many as three popes presided over the Church concurrently during the Western Schism. The Church’s divisions weakened papal power and made it possible for state churches to emerge. The European economy and intellectual life were significantly impacted by the Ottoman Turks’ capture of Constantinople in 1453. [3]

The Hundred Years’ War

From 1337 to 1453, there was a war between France and England known as the Hundred Years’ War. Before it eventually ended with the expulsion of the English from France, with the exception of the Calais Pale, it was fought mostly over claims by the English kings to the French throne and was interspersed by many brief and two extended periods of calm. [3]

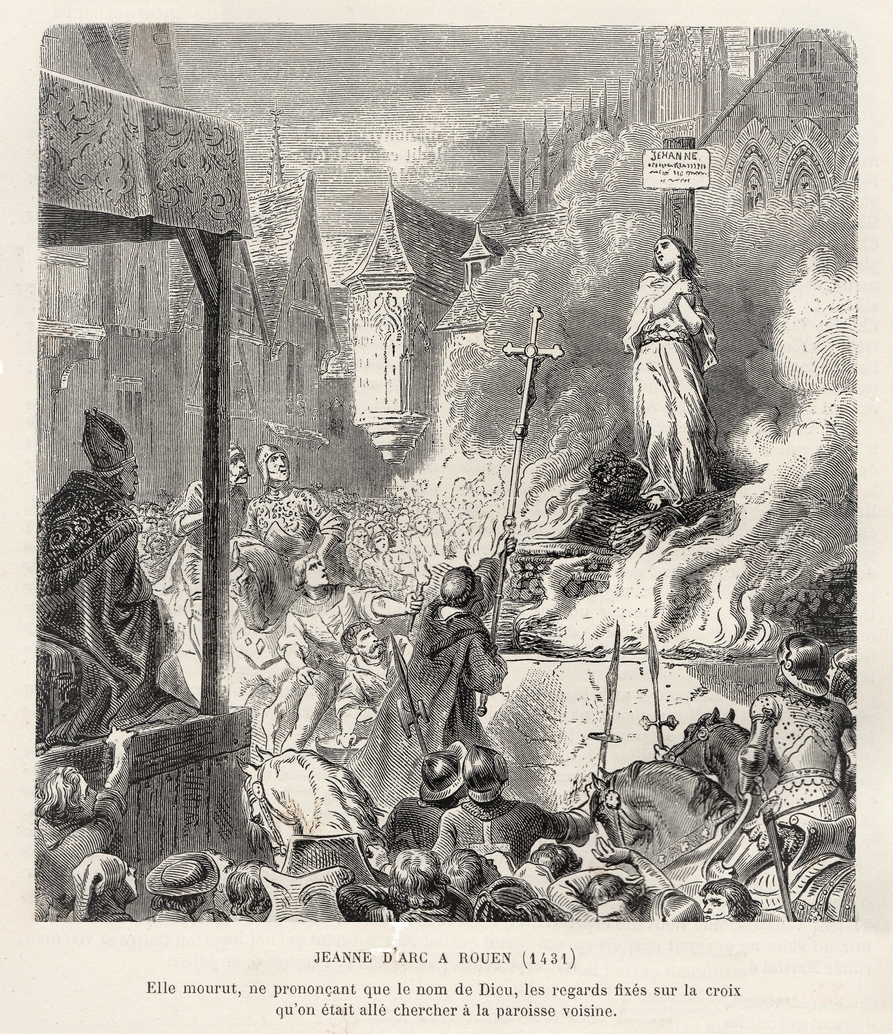

The Edwardian War (1337–1360), the Caroline War (1369–1389), the Lancastrian War (1415–1429), and the gradual decline of English fortunes after the apparition of Joan of Arc are considered to be the three or four phases of the war (1429-1453). The war gave rise to conceptions of French and English identity, despite being largely a dynastic fight. Military innovation resulted in the demise of the feudal system of armies dominated by heavy cavalry and the use of new weapons and strategies.

Peasants’ roles in the conflict were altered by the introduction of the first standing army in Western Europe during the period of the Western Roman Empire. It is frequently regarded as one of the most important battles in the development of medieval warfare because of all this and the length of its endurance. [3]

The Economy and Society in the Medieval Era

A system known as “feudalism” dominated rural life in medieval Europe, when the king gave bishops and noblemen control over vast tracts of land known as “fiefs.” The majority of the labor on the fiefs was performed by serfs, or landless peasants, who cultivated and gathered crops and gave the majority of the harvest to the landowner. They were given permission to reside on the land in return for their labor. In the event of a hostile invasion, they have also assured protection.[2]

The feudal system, however, started to shift in the 11th century. Fewer farm laborers were required as a result of agricultural inventions like the heavy plow and three-field crop rotation, which increased farming productivity and efficiency. However, population growth was enabled by the increased and improved food supply. As a result, towns and cities began to lure an increasing number of people. The Crusades also opened up new trade routes to the East and gave Europeans a taste for exotic imports like wine, olive oil, and expensive fabrics. Port cities particularly prospered as the commercial economy grew. Around 15 cities in Europe had a population of over 50,000 by the year 1300.

These cities saw the beginning of the Renaissance, a new era. Although the Renaissance was a period of profound intellectual and economic transformation, it was not a true “rebirth” because it had Middle Ages foundations.[2]

More Interesting Facts About the Medieval Era

In addition to learning about the key events that occurred in the Medieval Era, here are some of the other interesting facts about this period in history that you should learn about:

- Medieval times were not always easy, and this was true not only for people. All kinds of animals, including livestock and insects, were placed on trial if they were thought to have broken the law, just like their two-legged masters. According to E.P. Evans, the author of the book “The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals,” there are records of at least 85 animal trials that happened during the Middle Ages, and the stories range from tragic to ridiculous.

- The medieval aristocracy placed a high value on clothing since it served as a symbol of their wealth and general superiority to the underclass. As a result, strange fashion fads like long, pointed shoes for men spread throughout Europe. The longer the shoes, the wealthier the wearer and, thus, the higher their social standing. Some of the shoes required whalebone reinforcement because they were so lengthy.

- It’s true that upper-class marriages throughout the middle ages were frequently arranged for political and social reasons rather than for love, contrary to popular belief. In practically every facet of medieval society, women had no voice. In actuality, men and women were deemed to be physically prepared for marriage as soon as they entered puberty, which might be as early as 12 for girls and 14 for boys.

- In the middle ages, couples in Germany were quick to settle their differences. Instead of simply squabbling like any other regular couple would, they entered the ring. Trial by battle was a common method of resolving conflicts, and when man and wife fought, there were strange rules that applied, such as the husband had to stand in a hole with his hand behind his back while his wife ran around carrying a sack of pebbles.

- While many women today spend money on eyelash extensions, things were very different in the Middle Ages. Women would pluck their lashes and brows to draw attention to their foreheads, which were thought to be the focal feature of their faces. Some were so determined to have a flawlessly oval, bald face that they would pluck their hairlines.

- It makes sense that people in medieval times were worried about death, given how religious society was at the time and how many people were dying from the Black Death. As a result, the “ars moriendi” or “The art of dying” movement became popular. It should be a planned and peaceful death. The dying person should, like Christ, accept their fate without desperation, disbelief, impatience, vanity, or avarice.

- In the Middle Ages, peasants had jobs near where they resided. Their trade was kept within the family-owned business and was passed down from father to son. You would probably be a cobbler if your father had been one.

- Before the games had names, there was mob violence associated with sports in medieval England. Football, or soccer as it is known outside of the United States, was a violent, chaotic, and occasionally lethal sport. It could take place across entire towns, included an endless number of participants, and frequently engaged the other team rather than the ball. Any method, with the exception of actual murder, may be utilized to score in “Shrovetide football.” King Edward II, who was clearly more into golf, thought enough was enough and outlawed the game in 1314, stating, “under pain of imprisonment, such games to be employed in the city in future.”

- Although it may have seemed like a dreadful fate in the Middle Ages, jesters also had certain advantages. They were able to get away with slandering the lords and ladies of the court and expressing their political beliefs during a time when doing so was severely prohibited since everything they said was by royal decree and should be taken in “jest.” Even in the medieval court, being humorous was advantageous.

- Mythology and religion were the two things that medieval people loved most, and they sometimes blended the two in extremely strange ways. People often thought that the Bible compared Jesus to a unicorn because of a mistranslation of what was probably meant to be an ox. The unicorn—or whatever the medieval populace thought to be a unicorn—repeatedly appeared in medieval religious art as a result of how far they took this notion. The unicorn was also utilized as a strangely uncomfortable allegory of Christ entering his mother’s womb because only pure maidens were permitted to touch them.

Conclusion

Learning about medieval history is very useful. It is a period in history that provides a context for understanding the modern world in which we live. It is an essential era for the development in the field of culture, religion, art, and language. We hope this post helped you learn more about the timeline and key events of the Medieval Era.

References

[1] Britannica, E. T. (2021, May 6). Middle ages. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved August 5, 2022, from https://www.britannica.com/event/Middle-Ages

[2] History.com, E. (2010, April 22). Middle Ages. History.com. Retrieved August 5, 2022, from https://www.history.com/topics/middle-ages/middle-ages

[3] New World Encyclopedia, C. (2007). Middle Ages. New World Encyclopedia. Retrieved August 5, 2022, from https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Middle_Ages

[4] White, F. (2019, September 23). 12 bizarre medieval trends. LiveScience. Retrieved August 5, 2022, from https://www.livescience.com/12-bizarre-medieval-trends.html

[5] Hughes, T. (2021, October 15). 10 curious facts about life in medieval times. History Hit. Retrieved August 5, 2022, from https://www.historyhit.com/facts-about-life-in-medieval-times/