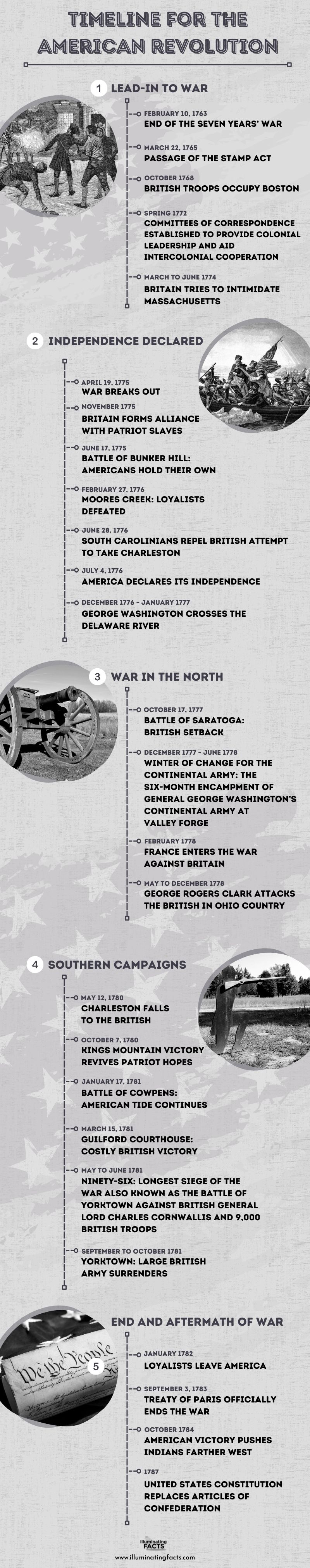

Table of Contents

The American Revolution is also known as the Revolutionary War, which occurred from 1775 to 1783. It was the revolution that arose from the growing tensions between residents of the 13 North American colonies of Great Britain and the colonial government, which represented the British Crown.[1] If you are looking to learn more about the things that occurred in the Revolutionary War, read on as we give you the timeline for the American Revolution.

Lead-In To War

Tensions had been building between colonists and the British authorities for more than a decade before the outburst of the American Revolution in 1775. The French and Indian War, which is more known as the Seven Years’ War, which occurred from 1756 to 1763, brought new territories under the power of the crown. However, the expensive conflict leads to new and unpopular taxes.[1]

The British government attempted to raise revenue by taxing the colonies. These were popularly known as the Stamp Act of 1765, the Townshend Acts of 1767, and the Tea Act of 1773. However, these attempts met with heated protests among colonists, who felt aggrieved about their lack of representation in Parliament. They demanded the same rights as other British subjects.

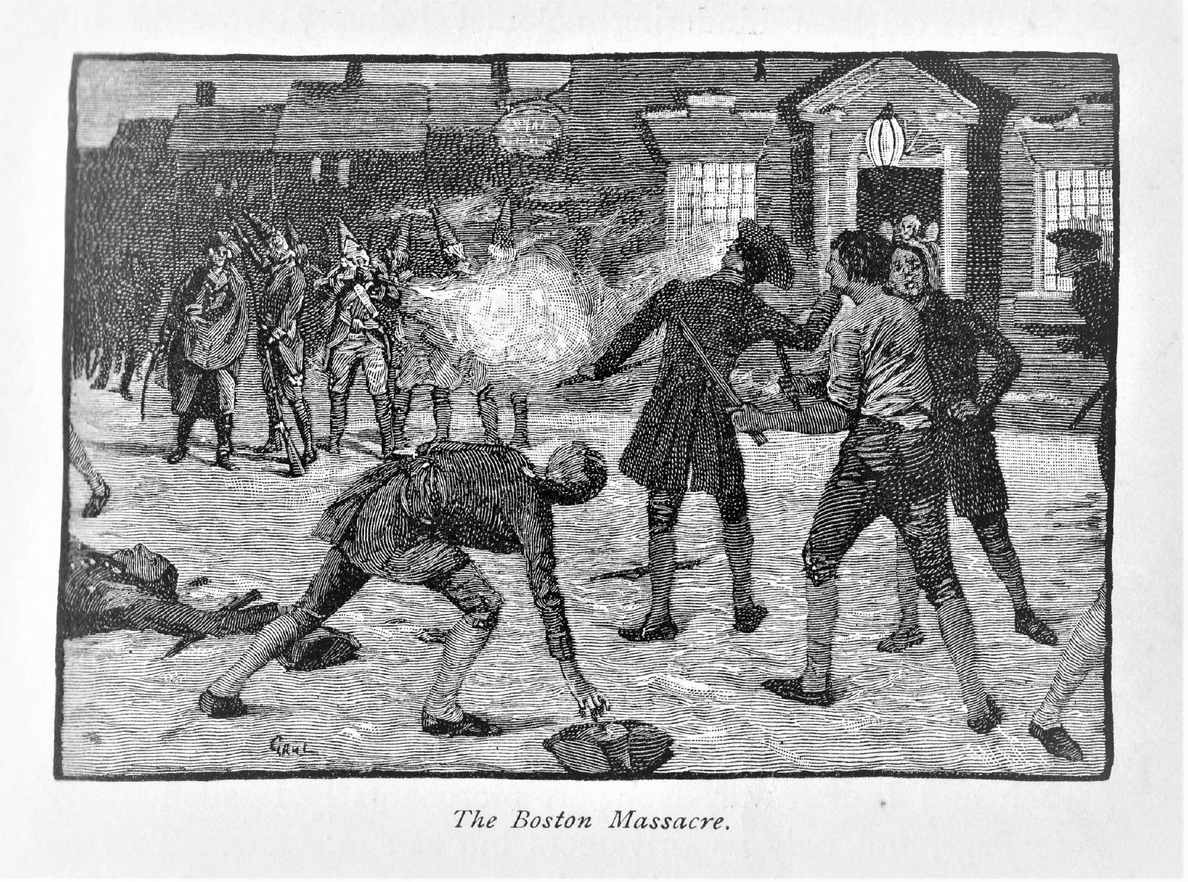

In 1770, colonial resistance led to violence. British soldiers opened fire on a multitude of colonists, which killed five men in what was popularly known as the Boston Massacre. A band of Bostonians changed their appearance to hide their identity. They boarded British ships and dumped 342 chests of tea into Boston Harbor during the Boston Tea Party. After December 1773, an outraged Parliament passed a series of measures, which are known as the Intolerable or Coercive Acts. These were designed to reassert imperial authority in Massachusetts.[1]

Patrick Henry of Virginia, John Jay of New York, George Washington of Virginia, John and Samuel Adams of Massachusetts, and other colonial delegates met in Philadelphia in September 1774 to give voice to the protests against the British crown. The First Continental Congress did not go so far as to demand independence from Britain. However, it condemned taxation without representation, along with the maintenance of the British army in the colonies without their permission. It issued a statement of the rights due to every citizen, which includes liberty, property, life, assembly, and trial by jury. The Continental Congress chose to meet again in May 1775 to consider further action. However, before that time came, violence had already begun.

Independence Declared

Hundreds of British troops marched to nearby Concord, Massachusetts, from Boston on the night of April 18, 1775, to seize an arms cache. The alarm was sounded by Paul Revere and other riders, and colonial militiamen started assembling to stop the Redcoats. Local militiamen clashed with British soldiers on April 19 in the Battles of Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts, which marked the “shot heard around the world” that indicated the beginning of the Revolutionary War.[1]

It is unclear who fired the first shot, but it sparked combat that left 8 Americans dead. The British were met by hundreds of militiamen at Concord. Outstripped and running low on bullets, the British column was forced to give up to Boston. During the return march, American snipers took a deadly toll on the British. In the Battle of Lexington and Concord, the total losses numbered 273 British and more than 90 Americans.[2]

When the Second Continental Congress assembled in Philadelphia, delegates, including Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin, voted to create a Continental Army, with Washington as the commander in chief. The first major battle of the Revolution occurred on June 17, and colonial forces perpetrated heavy fatalities on the British regiment of General William Howe at Breed’s Hill in Boston. This engagement was known as the Battle of Bunker Hill, which ended in a British victory, but loaned reassurance to the revolutionary cause.[1] Some 2,300 British troops cleared the hill of the engrained Americans, but at the cost of more than 40% of the assault force. Therefore, the battle was a moral victory for the Americans.[2]

Washington’s forces fought to keep the British confined in Boston throughout that fall and winter. However, artillery captured at Fort Ticonderoga in New York helped alter the balance of that struggle in late winter. In March 1776, the British evacuated the city, with Howe and his men retreating to Canada to prepare for a major invasion of New York.[1]

With the Revolutionary War in full swing by June 1776, a growing majority of the colonists had come to favor independence from Britain. The Continental Congress selected to adopt the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. It was drafted by a five-man board, which included Franklin and Adams, but it was mainly written by Jefferson. In the same month, the British government sent a large fleet together with over 34,000 troops to New York, determined to crush the rebellion.

In August 1776, Howe’s Redcoats routed the Continental Army on Long Island. By September, Washington was forced to evacuate his troops from New York City. On Christmas night, pushed across the Delaware River, Washington fought back with a surprise attack in Trenton, New Jersey, and won another victory at Princeton. It was to revive the rebels’ flagging hopes before making winter quarters at Morristown.[1] The victory of America at Trenton and in the Battle of Princeton on January 3, 1777, provoked the new country and kept the fight for independence alive.[1]

War In The North

The strategy of the British in 1777 included two main points of attack intended to separate New England, where the most widespread support was relished by the rebellion from the other colonies. To that end, the army of General John Burgoyne marched south from Canada to an intentional meeting with Howe’s militaries on the Hudson River.

In July, Burgoyne’s men dealt a devastating loss to the Americans by retaking Fort Ticonderoga, while Howe chose to move his troops southward from New York to confront the army of Washington near the Chesapeake Bay. On September 11, the British defeated the Americans at Brandywine Creek, Pennsylvania, and entered Philadelphia on September 25. In early October, before retreating to winter quarters near Valley Forge, Washington rebounded to strike Germantown.

On September 19, the move made by Howe had left the army of Burgoyne exposed near Saratoga, New York, and the British agonized over the penalties of this when an American force under General Horatio Gates overpowered them at Freeman’s Farm in the First Battle of Saratoga. After suffering another defeat at Bemis Heights on October 7, which was the Second Battle of Saratoga, Burgoyne yielded his remaining forces on October 17. The victory of America in the Battle of Saratoga would prove to be a turning point of the American Revolution. It was because it prompted France, which had been aiding the rebels secretly since 1776, to enter the war openly on the American side. However, it would not formally declare war on Great Britain until June 1778. The American Revolution started as a civil conflict between Britain and its colonies, but it turned into a world war.[1]

Southern Campaigns

Throughout the long, hard winter at Valley Forge, Washington’s troops profited from the training and discipline of Baron Friedrich von Steuben, the Prussian military officer sent by the French, and the leadership of Marquis de Lafayette, a French aristocrat. On June 28, 1778, Washington’s army attacked the British forces under Sir Henry Clinton, who attempted to withdraw from Philadelphia to New York, near Monmouth, New Jersey.

The battle ended efficiently in a draw, as the Americans held their ground. However, Clinton was able to get his army and supplies safely to New York. A French fleet directed by the Comte d’Estaing arrived off the Atlantic coast on July 8, and it was ready to combat with the British. In late July, a joint attack on the British at Newport, Rhode Island, was unsuccessful. Generally, the war settled into a drawing point in the North.

From 1779 to 1781, the Americans grieved a number of impediments. These include the defection of General Benedict Arnold to the British and the first serious mutinies within the Continental Army.[1] Having fought courageously in a number of battles earlier in the war, General Benedict Arnold united with the British to surrender the fort at West Point, New York, that he commanded. When John Andre, the British army officer whom Arnold had negotiated, was hanged as an infiltrator after he was apprehended and the plot revealed, Arnold took reservation with the British.[2]

By early 1779, in the South, the British occupied Georgia and seized Charleston, South Carolina, in May 1780. The British forces under Lord Charles Cornwallis then started an attack in the region, crushing Gates’ American troops at Camden in mid-August, even though the Americans won over Loyalist forces at King’s Mountain in early October. Gates was replaced by Nathanael Green as the American commander in the South in December of that year. General Daniel Morgan, under the command of Green, won against a British force under Colonel Banastre Tarleton on January 17, 1781, at Cowpens, South Carolina.[1]

After winning at the Guilford Courthouse, North Carolina, on March 15, 1781, Lord Cornwallis entered Virginia to join other British forces, setting up a base at Yorktown. Yorktown was placed under siege by the army of Washington and a force under the French Count de Rochambeau. On October 19, 1781, Cornwallis surrendered his army, which included over 7,000 men.[2]

End of the Revolutionary War and the Aftermath

After the British downfall at Yorktown, the land battles in America mostly died out. However, the clashes continued at sea, primarily between the British and European cronies of America, which included the Netherlands and Spain. The military judgment in North America was reflected in the initial Anglo-American peace treaty of 1782, which was comprised in the Treaty of Paris on September 3, 1783.

By its terms, Britain recognized the independence of the United States with liberal boundaries, as well as the Mississippi River on the west. Canada was retained by Britain, but East and West Florida were surrendered to Spain.[2] The Treaty of Paris endorses the independence of the 13 North American states. However, another war with England, which was from 1812 to 1815, was needed to truly secure the American nation.[3]

In October 1784, the Treaty of Fort Stanwix imposed peace on the members of the Iroquois Confederacy, which sided with the British in the Revolution. The aftermath of the war proved devastating to Native Americans. Indian tribes, without any European allies to depend upon, will be under growing pressure from colonists moving westward out of the original 13 states.

In 1787, a convention of states in Philadelphia proposed the Constitution to change the much looser central government functioning under the Articles of Confederation, which was adopted in 1777. The Constitution remains the framework of government in the United States, with amendments.[3]

References

[1] History.com Editors. (2009, October 29). Revolutionary War. History.com. Retrieved May 12, 2022, from https://www.history.com/topics/american-revolution/american-revolution-history

[2] Wallenfeldt, J. (2010). Timeline of the American Revolution. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved May 12, 2022, from https://www.britannica.com/list/timeline-of-the-american-revolution

[3] NPS.gov. (2021, January 4). Timeline of the Revolution. National Parks Service. Retrieved May 12, 2022, from https://www.nps.gov/subjects/americanrevolution/timeline.htm