The United States of America is not the only country to ever have a revolution, as the French had one too. The French Revolution is also known as the Revolution of 1789. It was a period of major social upheaval that started in 1787.[1] During this period, French citizens demolished and reformed the political landscape of their country, displacing centuries-old institutions like absolute monarchy and the feudal system. It was due to the discontent with the French monarchy and the poor economic policies of King Louis XVI. The French Revolution played an important part in shaping modern nations by presenting the world with the power integral to the will of the people.[2]

If you want to learn more about the events that happened during those times, we are here to help you. In this post, we are giving you the timeline of the French Revolution.

Source: https://examples.yourdictionary.com/french-revolution-timeline-simple-overview-major-events[3]

What Were the Causes of the French Revolution?

The expensive contribution of France to the American Revolution and the excessive spending by King Louis XVI and his forerunner had left the country on the edge of impoverishment as the 18th century drew to a close. In addition to the royal funds being exhausted, two decades of poor harvests, cattle diseases, high bread prices, and famine had ignited strife among peasants and the urban poor. A lot of people voiced their desperation and resentment through riots, lootings, and strikes, toward a regime that imposed heavy taxes but failed to provide any relief.

In the fall of 1786, Charles Alexandre de Calonne, the controller general of Louis XVI, proposed a financial reform package that comprised a universal land tax form wherein the privileged classes would no longer be exempted. To get support for these measures and foresee a growing upper-class revolt, the king subpoenaed the Estates-General, which was an assembly representing the clergy of France, nobility, and middle class, for the first time since 1614. Their meeting was scheduled for May 5, 1789. In the interim, delegates of the three estates from each vicinity would gather lists of complaints to present to the king.[2]

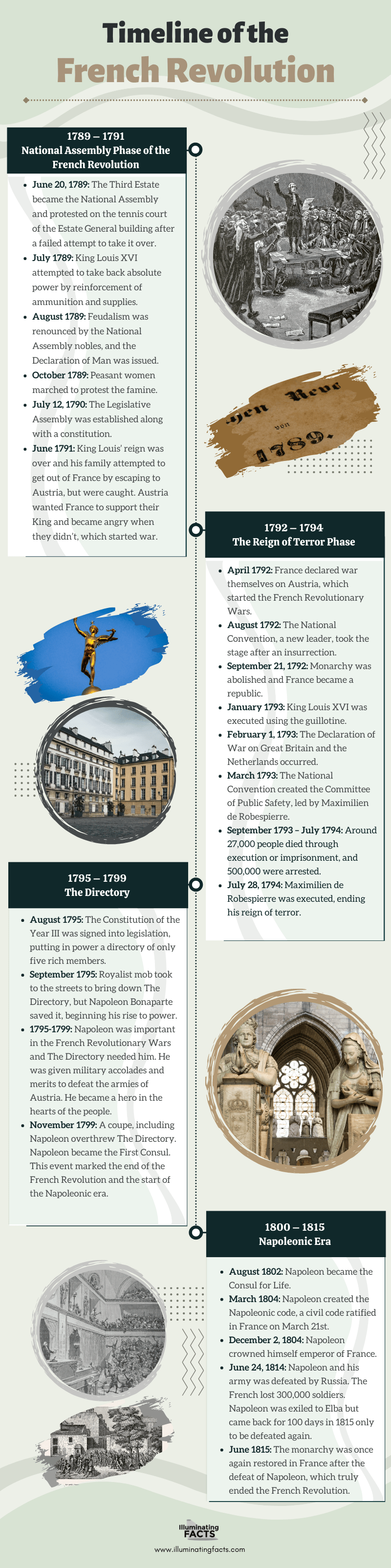

The National Assembly Phase of the French Revolution

The French people were not happy in 1789 due to the war and the spending habits of their king. The peasants had been through droughts and diseases, which made their harvest inadequate. They’ve had enough and began to revolt.

Rise of the Third Estate

A political party called The Third Estate required a change in the government. With this, several things occurred quickly, which led to making France a constitutional monarchy.[3] The non-aristocratic adherents of the Third Estate now embodied 98% of the people. However, they could still be outvoted by the other two bodies. In the lead-up to the May 5 meeting, the Third Estate specified to mobilize provision for equal representation and the abolition of the noble veto. This means that they wanted to vote by the head and not by status.[2]

Tennis Court Oath

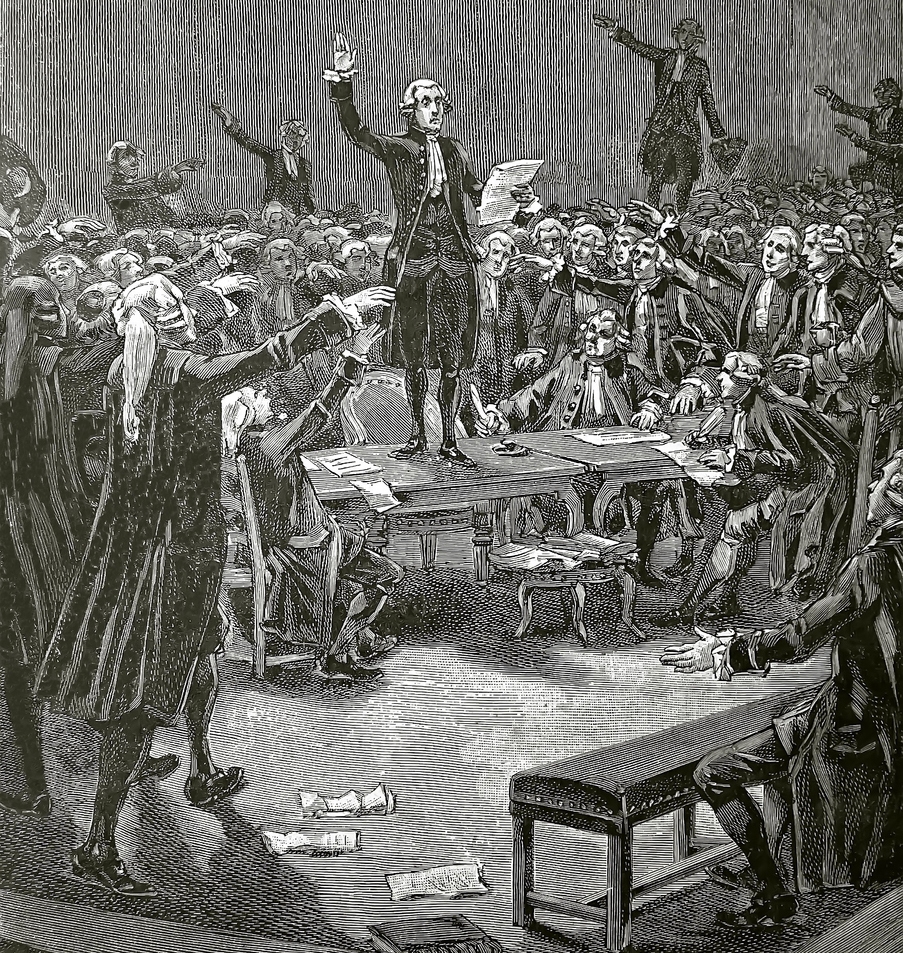

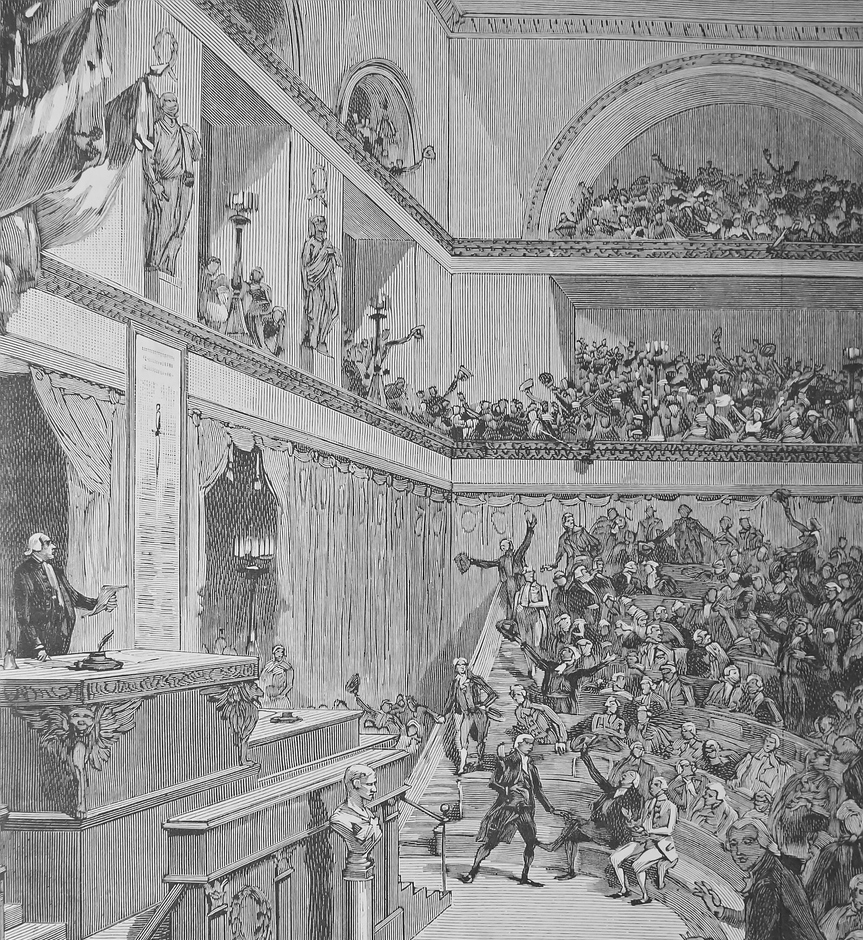

On May 5, 1789, the Estates-General met at Versailles. However, they were quickly divided over a vital issue, which was if they should vote by the head, giving the benefit to the Third Estate, or by the estate, wherein the two privileged orders of the monarchy might outvote the Third Estate. On June 17, the bitter fight over the legal issue finally drove the representatives of the Third Estate to declare themselves the National Assembly.[1]

After three days, they met on a close indoor tennis court and took the famous Tennis Court Oath, undertaking not to separate until constitutional modification had been attained. In a week, most of the clerical deputies and 47 liberal nobles joined them. Louis XVI reluctantly engrossed all three orders into the new assembly on June 27.[2] He urged the nobles and the remaining clergy to join the assembly, which took the official title of National Constituent Assembly on July 9. However, at the same time, he was starting to gather troops to dissolve it.[1]

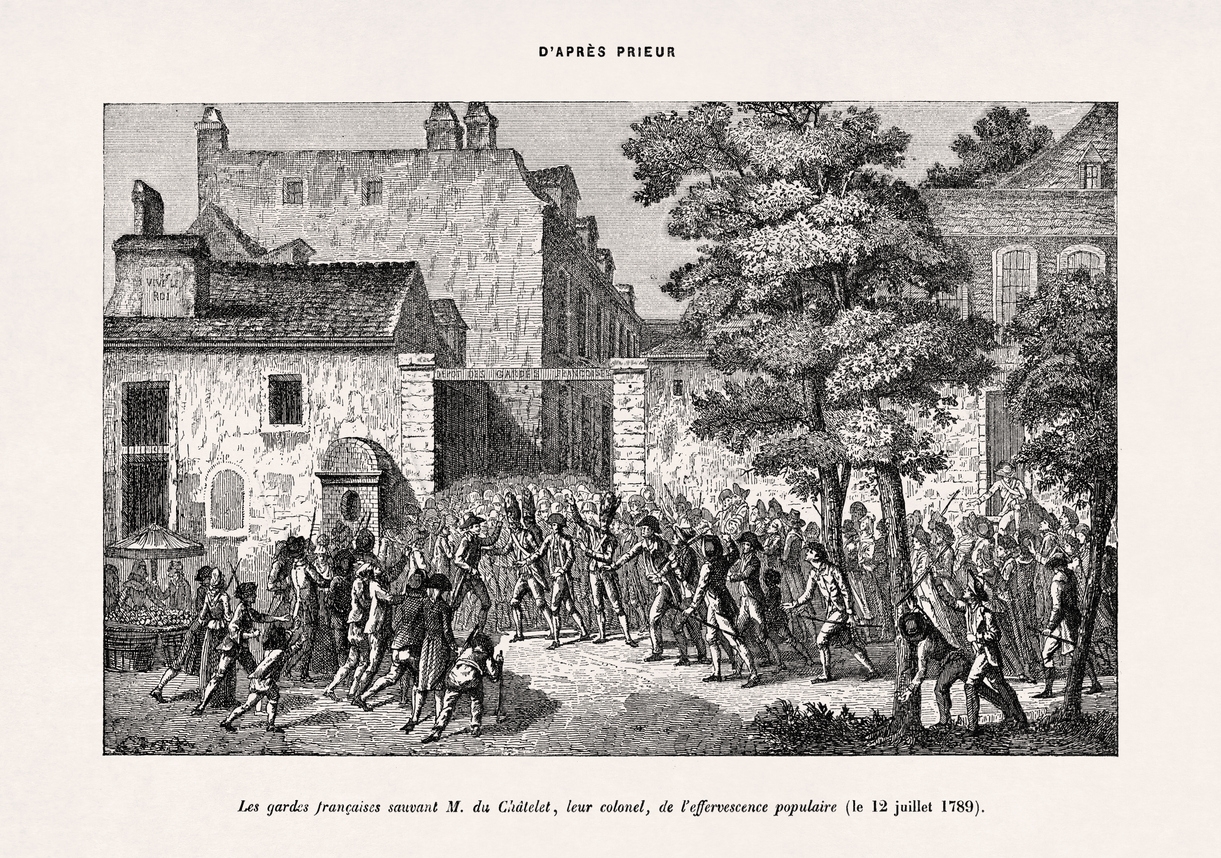

Storming the Bastille

In July 1789, gossip of an aristocratic scheme by the king and the privileged to take over the Third Estate led to the Great Fear, when the peasants were almost frightened. The insurrection was triggered in the capital due to the assembly of troops around Paris and the discharge of Necker. On July 14, 1789, the Parisian crowd seized the Bastille, which was a symbol of royal oppression. The king needed to yield again. He visited Paris and showed his gratitude for the power of the people by wearing a tricolor cockade.[1] On August 4, 1789, the agrarian insurrection hastened the growing exodus of nobles from the country and inspired the National Constituent Assembly to abolish feudalism.[2]

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

The Great Fear of July led the peasants in the provinces to rise against their lords. With this, the nobles and the middle class took fright. There was only one way for the National Constituent Assembly to check the peasants, which happened on the night of August 4, 1789, when it pronounced the eradication of the feudal regime and of the tax. On August 26, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen was introduced. It declared equality, liberty, the sacredness of property, and the right to resist oppression.[1]

Women’s March on Versailles

The pronouncements of August 4 and the Declaration were such revolutions that the king declined to sanction them.[1] On October 5, 1789, the Parisians, particularly the peasant women, rose again and marched to Versailles to protest the famine. The King, along with Marie Antoinette and their children, hid after Marie Antoinette purportedly expressed her famous words, “Let them eat cake,” which angered the crowd.[3]

The following day, the royal family was transported back to Paris. The National Constituent Assembly followed the court. In Paris, it continued to work on the new constitution. The French people joined actively in the new political culture made by the Revolution. Lots of uncensored newspapers kept them well-informed of events. There were also political clubs that permitted them to voice their opinions.[1]

Civil Constitution of the Clergy

The National Constituent Assembly accomplished the abolition of feudalism. It also stifled the old orders and established civil equality among men. In addition to that, it made more than half the adult male population qualified to vote, but only a few men met the conditions needed for becoming a deputy.[1]

After several months of enquiring what they wanted their government to look like, on July 12, 1790, the Legislative Assembly was established, along with a constitution. Aside from creating a limited monarchy, it also worked to separate the government from the church.[3] This was referred to as the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, which was rejected by Pope Pius VI and by many of the French priesthood. This created division that intensified the violence of the associated disagreements.[1]

Escape of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette

The intricate administrative system of the ancient regime was swept away by the National Constituent Assembly, which replaced a rational system based on the partition of France into departments, districts, cantons, and communes managed by elected assemblies. In addition to that, the ideologies underlying the administration of justices were also changed drastically. The system was adapted to the new administrative divisions. Suggestively, the judges were to be voted.

The National Constituent Assembly attempted to make a monarchial government wherein the legislative and executive powers were shared between the king and an assembly. It might have worked if the king had really desired to rule with the new ruling classes. However, King Louis XVI was feeble and hesitant and was a prisoner of his patrician counselors.[1] He knew that his reign was over. With this, he and his family tried to get out of France and go to Austria. However, they were caught. Austria wanted France to back their King. However, when France declined, they became angry, which ignited a war.[3]

The Reign of Terror Phase of the French Revolution

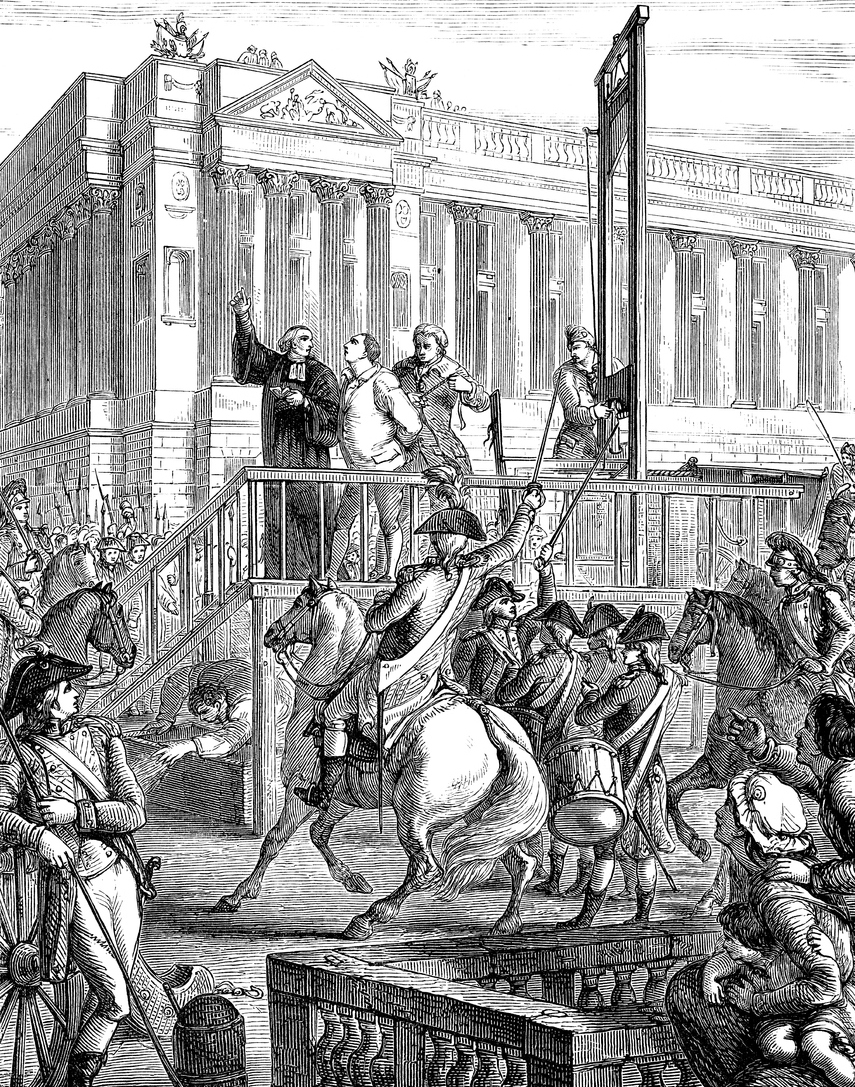

After the King and Marie Antoinette attempted to escape, things became a bit intense in France. Since France did not want to listen to Austria, France was the one to declare war. Society saw King Louis XVI as a traitor, and he was removed as the king, which made France a republic. However, that was not enough to appease the people. The king was executed using the guillotine, which led to the true Reign of Terror.[3]

France’s Declaration of War

The monarchies around Europe did not like the way France overthrew Louis XVI. However, they were also not going to unite in war.[3] By early 1792, both radicals were eager to spread the principles of the Revolution, and the king, hopeful that war would either allow foreign armies to rescue him or strengthen his authority, supported an aggressive policy. On April 20, 1792, France declared war against Austria.[1] This started the French Revolutionary Wars.

The First Phase of the War: Fall of Legislative Assembly and Abolishment of Monarchy

From April to September 1792, France was defeated. In July, Prussia joined the war, and an Austro-Prussian army crossed the frontier and quickly advanced toward Paris. Marie Antoinette, believing that they had been betrayed by the monarchy, privately invigorated her brother, Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II, to conquer France as a counter-revolutionary measure.

On August 10, 1792, the Paris revolutionaries rose, inhabiting the Tuileries Palace, where Louis XVI was living. They restrained the royal family in the temple. At the start of September, the Parisian crowd broke into the prisons and slaughtered the aristocrats and clergy that were held there. In the interim, volunteers were pouring into the army as the Revolution had stirred French nationalism.[1]

While the Legislative Assembly succeeded in getting rid of the king and starting a war, they did not succeed in staying in power. The National Convention, a new leader, took the state on September 20, 1972, after the insurrection that occurred in August.[3] The National Convention declared the abolition of the monarchy and the formation of the French republic.[2]

The Second Phase of the War: The Execution of King Louis XVI

The second phase of the war occurred from September 1792 to April 1793. Belgium, Savoy, the Rhineland, and the county of Nice were seized by French armies. The National Convention, on the other hand, was divided between the Girondins, who wished to organize a middle-class republic in France and to spread the Revolution to the whole of Europe.

Despite the efforts made by the Girondins, Louis XVI was judged by the Convention. He was brought up to court for his crimes. On January 21, 1793, he was executed using the guillotine for treason. Nine months later, Marie Antoinette also met the same fate.[1]

The Third Phase of the War: Declaration of War on Britain

The Reign of Terror Begins

The National Convention formed the Committee of Public Safety in March of 1793. It was a witch-hunt committee led by Maximilien de Robespierre. He worked to find and eradicate those who might attack the new nation.[3] This was the start of the Reign of Terror, a 10-month period wherein suspected enemies of the revolution were guillotined by the thousands.[2]

In June 1793, the Jacobins held control of the National Convention from the more reasonable Girondins. They inaugurated a series of radical measures, which comprised the formation of a new calendar and the abolition of Christianity.[2]

From September 5, 1793, to July 28, 1794, there were around 27,000 people who died by execution or incarceration, and around 500,000 were detained.[3] At the same time, the revolutionary government raised an army of more than one million men.[1]

The Fourth Phase of the War: End of the Reign of Terror

The fourth phase of the war starts in the spring of 1794. On June 26, 1794, France won against the Austrians at Fleurus, which allowed the French to reoccupy Belgium. This triumph made the Reign of Terror and the economic and social limitations seem pointless. On July 27, 1794, Robespierre was ousted in the National Convention and was executed the next day, July 28, 1794.

After the fall of Maximilien de Robespierre, the social laws were no longer applied, and efforts toward economic equality were unrestricted. The National Convention started to discuss a new constitution. On the other hand, in the west and in the southeast, a royalist “White Terror” broke out. They even tried to seize power in Paris, but they were crumpled by General Napoleon Bonaparte on October 5, 1795. After a few days, the National Convention was disseminated.[1]

The Directory and Revolutionary Expansion

For some, the end of the Reign of Terror was the end of the French Revolution. However, there were still revolutionary things occurring within the government. In the last two phases of the French Revolution, Napoleon Bonaparte played a vital part.[3]

On August 22, 1795, the Constitution of the Year III was signed into legislation.[3] With this, executive power would lie in the hands of a five-member Directory appointed by parliament. Jacobins and Royalists protested the new regime, but they were swiftly silenced by the army, which was led by a young and successful General Napoleon Bonaparte.[2]

However, the Directory was not doing a great job, and people became furious. A royalist mass took to the streets to bring it down. But on September 21, 1795, Napoleon Bonaparte saved the Directory, which started his rise to power.[3]

The Napoleonic Era

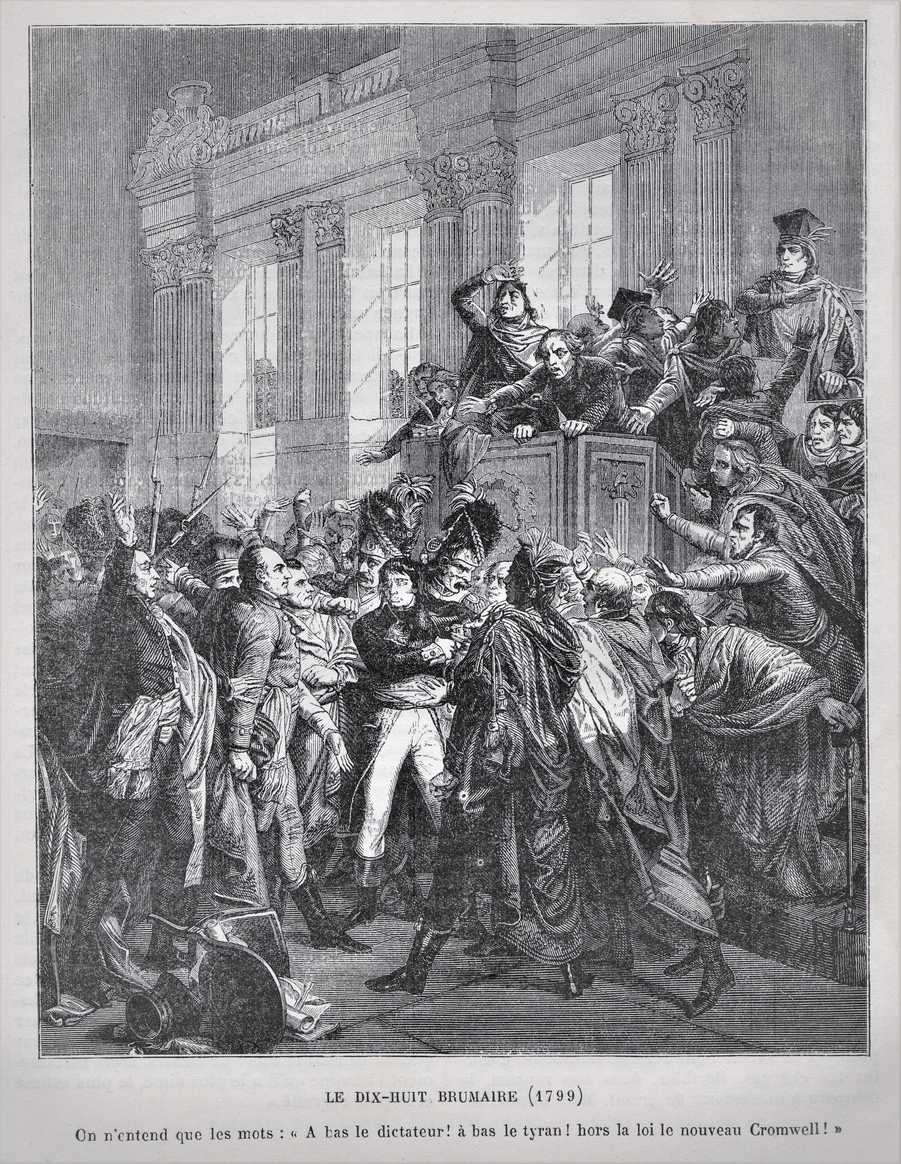

This regime, a bourgeois republic, might have reached solidity if the war did not prolong the struggle between revolutionaries and counter-revolutionaries all over Europe. The war, furthermore, disaffected prevailing hatreds between the Directory and the legislative councils in France, which often gave upsurge to new ones. On September 4, 1797, these disagreements were settled by a coup d’état, which removed the monarchists from the Directory and from the councils. On November 9, 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte ended the Directory and led France as its “First Consul.” [1]

After he became the leader of France, he realized that a civil code was needed, which the people should follow. He created one and called it the Napoleonic Code, which was officially approved on March 21, 1804, in France. In addition to that, on December 2, 1804, Napoleon Bonaparte also crowned himself as the emperor of France, which allowed his authority in Europe to continue.

However, it is true that the higher you rise, the harder you fall. This lesson was learned by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1814. After he had a long and difficult battle with Russia, he and his army were defeated on June 24, 1814. The French lost 300,000 soldiers in the battles, as well as due to hunger and intense weather conditions. Napoleon was expatriated to Elba after their downfall. However, he came back for 100 days in 1815, only to be overpowered again. With the fall of Napoleon Bonaparte, the next of kin of Louis XVI mounted the throne once again. Monarchy was restored in France on July 8, 1815, which ended the French Revolution.[3]

References

[1] Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. (2020, September 10). French revolution. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved May 18, 2022, from https://www.britannica.com/event/French-Revolution

[2] History.com Editors. (2009, November 9). French Revolution. History.com. Retrieved May 18, 2022, from https://www.history.com/topics/france/french-revolution

[3] Betts, J. (n.d.). French revolution timeline: Simple overview of major events. Examples. Retrieved May 18, 2022, from https://examples.yourdictionary.com/french-revolution-timeline-simple-overview-major-events