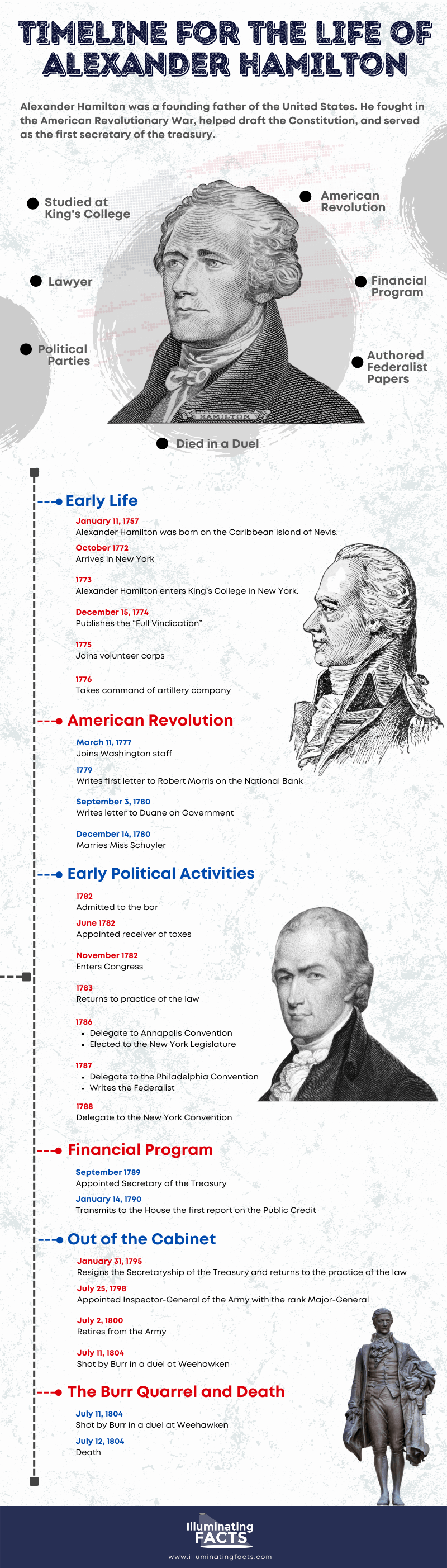

Alexander Hamilton was a founding father of the United States. He fought in the American Revolutionary War, helped draft the Constitution, and served as the first secretary of the treasury. He was also the founder and chief architect of the American financial system. In this post, we are going to take a look at the timeline of the important events in his life and his legacy.

Early Life

Alexander Hamilton was born in either 1755 or 1757 on the Caribbean island of Nevis. His father was James Hamilton, a Scottish trader, and his mother was Rachel Fawcett Lavine. However, his parents were not married as Rachel was still married to another man when Alexander was born. She had left her husband after he spent much of her family fortune and had her imprisoned for adultery.

Unfortunately, in 1766, Hamilton’s father abandoned their family, followed by the death of his mother after two years. When he was just 11, he was hired as a clerk in a trading company on St. Croix. In 1772, he gained wider attention when he published an eloquent letter describing a hurricane that had hit the island.[1]

Locals worked together to raise money for Hamilton to send him to America to study. In 1772, he arrived in New York. Hamilton’s ability, industry, and engaging manners won him advancement from bookkeeper to manager. Later on, friends sent him to a preparatory school in Elizabethtown in New Jersey.

In the autumn of 1773, he entered King’s College, which was later Columbia, in New York. Since he was very ambitious, he became a successful student. However, his studies were interrupted by the growing revolt against Great Britain. Hamilton publicly defended the Boston Tea Party, wherein Boston colonists destroyed several tea cargos in defiance of the tea tax.

From 1774 to 1775, Alexander Hamilton wrote three important pamphlets, which upheld the agreements of the Continental Congress on the non-importation, non-consumption, and non-exportation of British products attacked by British policy in Quebec. Those anonymous publications, wherein one of them ascribed to John Jay and John Adams, which were two of the brightest American propagandists, gave the first solid evidence of the cleverness of Hamilton.[1]

American Revolution

When the revolutionary war started, Alexander Hamilton was commissioned to lead the provincial artillery in the Continental Army.[2] He organized his own company, and during the Battle of Trenton, when he and his men under Lord Cornwallis prevented the British from crossing the Raritan River and attacking George Washington’s main army, showed noticeable bravery.[1]

In February 1777, Alexander Hamilton captured the attention of General George Washington, the army’s commander-in-chief, who gave him a position on his staff.[2] He was invited by Washington to become an aide-de-camp with the rank of lieutenant colonel. In his four years on Washington’s staff, he became close to the general and was trusted with his communication. Hamilton was sent on important military missions. Since he had a fluent command of French, he also became a cooperation officer between Washington and the French generals and admirals.[1]

Alexander Hamilton was eager to link himself with influence and wealth. With this, he married Elizabeth Schuyler on December 14, 1780. She was the daughter of Gen. Philip Schuyler, the head of one of the most distinguished families of New York. In the intervening time, becoming tired of the routine duties at headquarters and desire for glory, he pressed Washington for an active command in the field. However, Washington refused his request.

In early 1781, Hamilton seized upon a trivial quarrel to break with the general and leave his staff. Luckily, he had not forfeited the friendship of the general. In July of the same year, Washington gave him command of a battalion. In October, Hamilton led an assault on a British stronghold at the siege of the army of Cornwallis at Yorktown.[1] In November of the same year, Hamilton left active military service.[3]

Early Political Activities

Hamilton analyzed the financial and political weaknesses of the government in letters to a member of Congress and to Robert Morris, the superintendent of finance. In November of 1781, after the war, Hamilton moved to Albany, where he studied law. He was admitted to practice in July 1782.

After a few months, the New York legislature elected him to the Continental Congress. He continuously argued in essays for a strong central government. From November 1782 to July 1783, he worked for the same end in Congress, being persuaded that the Articles of Confederation were the cause of the weakness and disunion of the country.[1]

Alexander Hamilton started to practice law in New York City in 1783. He defended unpopular loyalists who had stayed authentic to the British during the Revolution in suits brought in contrast to them under a state law referred to as the Trespass Act. Comparatively, as a result of his efforts, the state acts expelling loyalist lawyers, and disfranchising loyalist voters were revoked.

In the same year, Hamilton also won the election to the lower house of the New York legislature and took his seat in January 1787. The legislature had appointed him a delegate to the convention in Annapolis, Maryland. It was met in September 1786 to consider the commercial dilemma of the Union. He suggested that the convention surpass its delegated powers and organize another meeting of representatives from all the states to address different deliberate problems challenging the nation. He created the draft of the address to the states from which emerged the Constitutional Convention that met in May 1787 in Philadelphia. After he persuaded New York to send a delegation, he obtained a place for himself on the delegation.[1]

Hamilton went to Philadelphia as an unbending nationalist who wanted to replace the Articles of Confederation with a strong centralized government. However, he did not partake much in the debates. He instead served on two essential committees. One was on rules at the beginning of the convention, and the other was on style at the end of the convention.[1] On June 18, he famously made a six-hour speech about his own plan for a strong and centralized government. He even drew criticism that he wanted to create a monarchy.[2]

Under his plan, the national government would have had unlimited power over the states. It had little impact on the convention. The delegates went ahead to frame a constitution that, while it provided strong power to a federal government, had some chance of being accepted by the people. The two other delegates from New York, who were strong opponents of a Federalist constitution, had withdrawn from the convention. With this, New York was not officially presented, and Hamilton had no power to sign for his state. Nevertheless, though he knew that his state wanted to go no further than a revision of the Articles of Confederation, he signed the new constitution as an individual.[1]

The Constitution was quickly attacked by opponents in New York. Hamilton answered them in the newspapers using the signature Caesar. Since the letters of Caesar seemed not persuasive, Hamilton used another classical pseudonym, Publius, as well as two collaborators, James Madison, a delegate from Virginia, and John Jay, the secretary of foreign affairs, to write “The Federalist.” It was a series of 85 essays in defense of the Constitution and republican government that emerged in newspapers from October 1787 to May 1788.[1] He wrote at least 51 of these Federalist Papers, and they would become his best-known writings.[2]

Some of the most important essays interpreted the Constitution and explained the powers of the executive, the senate, and the judiciary. It also explained the theory of judicial review or, for example, the power of the Supreme Court to declare legislative acts unconstitutional and, thus, invalid. Even though it was written and published in a rush, “The Federalist” was read by a lot of people, and it had a huge influence on contemporaries. It became one of the classics of political literature as well as helped in shaping American political institutions.[1]

Hamilton was reappointed as a delegate to the Continental Congress from New York in 1788. During the ratification convention in June, he became the chief champion of the Constitution. He won approval for it against strong opposition.

Financial Program

Washington was one hundred percent elected as the first president of the United States in 1789. He then appointed Hamilton as the first secretary of the United States Treasury.[2] Congress asked him to create a plan for the “adequate support of the public credit.” Envisioning himself as something of a prime minister in the official family of Washington, he created a bold and masterly program made to build a strong union, one that would weave his political philosophy into the government. The immediate objectives of Hamilton were to establish credit at home and abroad, as well as to fortify the national government at the expense of the states. From 1790 to 1791, he outlined his program in four notable reports to Congress.[1]

On January 14, 1790, he submitted the first two Reports on the Public Credit. On December 13, 1790, he counseled the subsidy of the national debt at full cost, the assumption in full by the national government of arrears acquired by the states during the Revolution, and an organization of taxation to pay for the assumed arrears. His motive was as much radical as economic. Through imbursement by the central government of the debts of the states, he anticipated binding the men of wealth and influence, who had attained most of the locally held bonds, to the national government.

However, powerful opposition arose to the funding and assumption scheme that Hamilton was able to push through Congress only after he bargained with Thomas Jefferson, who was the secretary of state during that time. That was when he gained Southern votes in Congress for it in exchange for his own backing in positioning the future national capital on the banks of the Potomac.[1]

The third report of Hamilton was the Report on a National Bank, which was submitted on December 14, 1790. It advocated the First Bank of the United States, which was modeled on the Bank of England.[2] With it, he wished to solidify the partnership between the government and the business classes who would benefit most from it, as well as to further advance his program to strengthen the national government.[1]

When Congress passed the bank charter, Hamilton convinced Washington to sign it into law. He progressed the argument that the Constitution was the source of implied and enumerated powers and that, via insinuation, the government had the right to charter a national bank as a proper means of regulating the currency. In later years, this doctrine of implied powers became the basis for interpreting and expanding the Constitution.

The fourth, longest, most multifaceted, and most visionary of Hamilton’s reports was submitted on December 5, 1791, which was the Report on Manufactures. In this report, he projected to aid the growth of infant industries through different protective laws. It included his idea that the general welfare needed the reassurance of manufacturers and that the federal government was indebted to direct the economy to that end. When he wrote this report, he leaned heavily on “The Wealth of Nations,” which was written by Adam Smith, a Scottish political economist, in 1776. However, he revolted against the idea Smith called laissez-faire, wherein the state must keep its hands off the economic procedures, which meant that it could give no tariffs, bounties, and other aid. However, the report had greater appeal to future generations than to the contemporaries of Hamilton, as Congress did nothing with it.[1]

Political Parties

The emergence of the national political parties was the result of the struggle over the program of Hamilton and the issues of foreign policy. Hamilton also had deplored parties like Washington, equating them with disorder and instability. He had aimed to establish a government of superior persons who would be above the party. However, he became the leader of the Federalist Party. It was a political organization in large part dedicated to the support of his policies. He chose to lead that party as he needed organized political support and strong leadership in the executive branch to get this program through Congress.

The Republican party was the political organization that challenged the Hamiltonians, which later became the Democratic-Republican Party. It was established by James Madison, a member of the House of Representatives, and Thomas Jefferson, Secretary of State.

The Federalists preferred close ties with England, while the Republicans chose to strengthen the old connection to France. In aiming to carry out his program, Hamilton restricted Jefferson’s domain of foreign affairs. Loathing the French Revolution and the democratic doctrines it laid, Hamilton tried to prevent Jefferson’s policies that might help France or injure England and to induce Washington to follow his own ideas in foreign policy.

He went as far as warning British officials of the attachment of Jefferson to France and to suggest that they evade the secretary of state and instead work through himself and the president when it comes to foreign policy. His move, along with other parts of his program, led to a feud with Jefferson. The two men endeavored to drive each other from the cabinet.

When the war between England and France started in February 1793, Hamilton wanted to use it as an excuse for abandoning the French alliance of 1778 and navigating the United States closer to England. However, Jefferson insisted that the alliance was still binding. Hamilton’s advice was essentially accepted by Washington. In April, he issued a proclamation of neutrality that was mostly understood as pro-British.

British commandeering of United States ships trading with the French West Indies and other protests led to popular demands for war counter to Great Britain, which was opposed by Hamilton. For him, such a war would be national suicide as his program was anchored on trade with Britain and on the import duties that supported his funding system.

Hamilton convinced the president to send John Jay to London to convey a treaty. The instructions for Jay were written by Hamilton. He also manipulated the negotiations and defended the unpopular treaty that Jay brought back in 1795, popularly in a series of newspaper essays he wrote under the name Camillus. The treaty was able to keep the peace, and it also saved Hamilton’s system.[1]

Out of the Cabinet

On January 31, 1795, Hamilton left his Treasury post and went back to his law practice in New York. However, his influence as an unofficial adviser remained. When Washington finished his two terms, Hamilton wrote the majority of his farewell address, which memorably cautioned about the risks of undue political bigotry and foreign influence. Hamilton continuously exerted influence behind the scenes in the administration of John Adams, Washington’s successor. The hostility between them would divide the Federalist party and help ensure victory for Jefferson in the 1800 presidential election.[2]

Before that, any hope that Hamilton had of acquiring the highest office in the nation had been ruined when he was involved in the first prominent sex scandal in America. In 1797, the infamous Reynolds Pamphlet was published. Hamilton went public with his issue with a wedded woman named Maria Reynolds to clean his name from any doubt of illegal financial rumors involving her husband, James.[2]

When France broke its relations with the U.S., Hamilton stood firm but not immediate war. However, when the peace mission that President Adams had sent to Paris in 1798 failed, followed by the publication of dispatches insulting U.S. sovereignty, Hamilton wished to place the country under arms. However, Adams resisted his requests. But in September 1798, Washington forced Adams to make Hamilton second in command of the army, which was the inspector general with the rank of major general. Adams never forgave Hamilton for this humiliation.[1]

Through independent peacekeeping, Adams kept the disagreement from spreading and, at the order of Congress, dispersed the provisional army. In June 1800, Hamilton resigned his commission. Adams, on the other hand, had purged his cabinet of those he regarded as “Hamilton spies.”

In revenge, Hamilton tried to prevent the re-election of Adams. In October 1800, he circulated a personal attack on Adams privately, which was “The Public Conduct and Character of John Adams, Esquire, President of the United States. The Republican contender for vice president and Hamilton’s enemy, Aaron Burr of New York, obtained a copy and had it published. With that, Hamilton was obliged to acknowledge his authorship and bring his quarrel with Adams into the open. It was a feud that revealed a permanent division in the Federalist Party.

Both Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr won the election. However, since both of them got an equal number of electoral votes, the choice between them for president was brought into the House of Representatives. Since the Federalists hated Jefferson, they wanted to throw the election to Burr. However, Hamilton helped to persuade them to choose Jefferson instead. When he supported his old Republican enemy, who later won the presidency, he lost prestige with his own party, which virtually ended his public career.[1]

The Burr Quarrel and Death

Aaron Burr and Hamilton had been political opponents since the debate over the Constitution back in 1789. Hamilton was angered by Burr further by running successfully against Philip Schuyler, which was Hamilton’s father-in-law, for the U.S. Senate in 1791. In 1792, Hamilton wrote that he feared Burr was corrupt both as a public and private man. He also added that he feels it a sacred duty to oppose his career.[2]

In 1804, largely sidelined by Jefferson as vice president, Burr decided to run for governor of New York. When he lost due to the opposition of powerful party rivals, he fixated his frustration on a newspaper article, which was published during the gubernatorial campaign. It claimed that Hamilton had insulted him at a private dinner. With this, he wrote to Hamilton, confronting him about the insult. Hamilton naturally refused to back down when Burr challenged him to a duel.

Hamilton and Burr met on the fighting ground in Weehawken, New Jersey, on July 11, 1804. Both of them fired, but Hamilton’s shot missed. In fact, historians believed that Hamilton never intended to hit Burr. However, Burr’s bullet wounded Hamilton mortally, which caused him to die the next day.

After many centuries, the legacy of Alexander Hamilton became popular with the debut of the groundbreaking musical titled “Hamilton.” It was written by and starred Lin-Manuel Miranda. It offered a new perspective on the Founding Father’s biography. In the 2016 Tony’s, it won 11 awards. In 2020, a filmed variety of the musical premiered on Disney+.[2]

References

[1] DeConde, A. (2021, July 8). Alexander Hamilton. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved May 11, 2022, from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Alexander-Hamilton-United-States-statesman#ref2989

[2] History.com Editors. (2009, November 9). Alexander Hamilton. History.com. Retrieved May 11, 2022, from https://www.history.com/topics/american-revolution/alexander-hamilton

[3] American Experience. (2021). Alexander Hamilton Chronology. PBS. Retrieved May 11, 2022, from https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/alexander-hamilton-chronology/