Introduction

Get to know about the world’s only Jewish state in modern times – Israel, or officially, the State of Israel.

It is a country in West Asia, bounded in the northwest by the Mediterranean Sea, north by Lebanon, northeast by Syria, southeast by Jordan, and southwest by Egypt.

Israel belongs to the Asian continent and is part of the Middle Eastern region. Israel is a small country compared to its neighbors – only 8,522 square miles (22,145 square kilometers), about the size of New Jersey, U.S.A. However, its topography is surprisingly rich and diverse, from the arid deserts in the south to the sand beaches stretching along the Mediterranean coast to the snow-capped mountains in the north. It has probably to do with its unique geographical location as Israel lies at the junction of the three continents: Asia, Africa, and Europe.

Jerusalem is one of the world’s most ancient cities and has long been considered the “holy city” by Jews, Christians, and Muslims. It is Israel’s seat of government and proclaimed capital, although the country’s sovereignty over the city has not received wide recognition. Since 1967, Jerusalem has been entirely under Israel’s rule, although up to this day, both Israelis and Palestinians still claim it as their capital. Neither claim has been wholly recognized by the international community.

Speaking of recognition, Israel’s status as an independent state has also been a point of contention among other nations. As of December 2020, at least 167 of the 193 member states of the United Nations formally recognize Israel. The rest – predominantly Arab or Muslim nations – do not recognize Israel’s status as an independent state, apart from not having diplomatic relations with it. Thus, such countries do not welcome Israelis to travel in their land and do not also accept Israeli passports, with very few exceptions.

After Jerusalem, the two other biggest cities in Israel are Tel Aviv and Haifa, and each of them has its own unique distinction:

Tel Aviv (or Tel Aviv-Yafo), located on the Mediterranean coast, is more secular than Jerusalem. Israel’s economic and technological center is home to thousands of tech companies and startups, including Waze and Fiverr. Tel Aviv also has the reputation of being the “party capital” and the “city that never sleeps” due to its thriving nightlife and 24-hour culture. It is also the “Vegan Capital of the World” for its 400-or-so vegan or vegan-friendly restaurants across the city.

Haifa is a city in northern Israel, built on the slopes of Mount Carmel, descending towards the Mediterranean coast. It is a port and industrial city and home to the Baha’i religion. Two of the world’s most renowned universities, the University of Haifa and the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, are located in Haifa. Its most famous landmark is the resplendent Baha’i shrine and its perfectly symmetrical gardens surrounding it, both of which were ingeniously built on the mountain slopes.

The 120-member Knesset (Hebrew for “assembly” or “gathering”) is Israel’s unicameral parliament and supreme authority. It enacts all the laws, elects the president and prime minister (although the President makes the ceremonial appointment for the Prime Minister), approves the cabinet, and supervises the work of the government, among many other things. The head of government is the Prime Minister, and the head of state is the President.

Currently, Israel has a population of over eight million, most of them Jewish. This little Middle Eastern country is big on history that dates from pre-biblical times, with the ensuing eras interspersed with periods of conflict, which are still ongoing up to this day.

In 2018, the Knesset adopted the Basic Nation-State Law, declaring Israel as the “nation-state of the Jewish people.” The new law also declared Hebrew as the only official language, downgrading Arabic, once also Israel’s official language, as having “a special status.” As expected, the then-newly ratified law fanned controversy. It didn’t sit well with critics, Israeli Arabs in particular, who blasted it as “racist” and “apartheid.” Former Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu defended the controversial legislation, saying it was “not a state of all its citizens but only of the Jewish people.” [1] He went on, saying that the new law had no relation to the rights of the individual as there were equal rights for all and that it dealt only with the fundamental issues on the rights of the Jewish people, the blue-and-white flag, the national anthem (“Hatikva”), and many others.

Despite being surrounded by enemies and constantly hounded by wars, threats of terrorism, and (wrongful) accusations of racism and apartheid, Israelis are proud that their country is the only democratic state in the Middle East. All of the country’s citizens – Jews, Muslims, Druze, Christians, Baha’i, people of other faiths, and even atheists – are free to practice their beliefs (or non-beliefs), enjoy full basic human rights, and have access to basic services, such as education and healthcare.

Despite suffering discrimination and persecution often since the ancient eras, the ancestral Jews had not given up hope of returning to their homeland one day. And it finally happened in 1948, when the State of Israel was established. Although the country is still hounded by conflict and questions from other countries regarding its statehood, Israel remains strong socially, economically, culturally, and militarily, among other things.

History

Early history

Most historians and scholars know Israel’s ancient history comes from the Hebrew Bible. The people of Israel – also called the “Jewish People” – trace their origins to Abraham, who established the belief that there is only one God, the creator of the universe.

Abraham, his son Isaac, and grandson Jacob are considered the forefathers of Judaism. Abraham is also regarded as the father of Islam (through his other son, Ishmael) and the spiritual ancestor of the Christians. Thus, Judaism, Islam, and Christianity are called “Abrahamic religions.”

Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob lived in the land of Canaan, which later became known as the Land of Israel. They and their spouses are buried in the Cave of the Patriarchs (Me’arat HaMakhpela) in the Old City of Hebron, West Bank, which lies 30 kilometers (19 miles) south of Jerusalem.

The word “Israel” comes from the name of Abraham’s grandson, Jacob, who was renamed “Israel” by God, according to the Hebrew Bible. [2] Jacob wrestled with a “man” who turned out to be – according to different interpretations – an angel or even God – who later gave him the name “Israel.” Interestingly, “Israel” means “God fights.” Israel’s tenacious fighting spirit has a biblical basis, indeed!

Source: Gerard van Honthorst, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

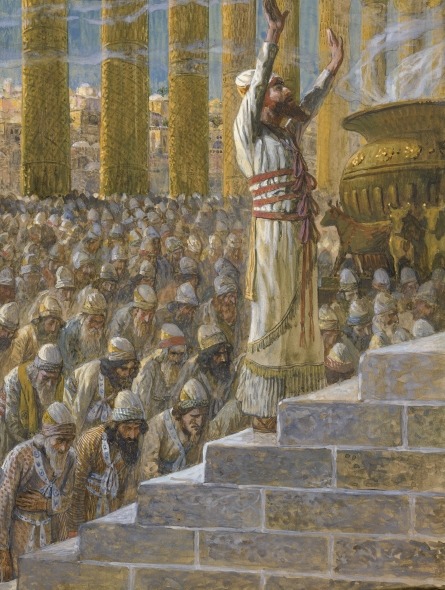

King David and King Solomon; the First Temple

The Hebrew Bible also tells the legend of King David, who gained fame after killing the giant Goliath, leading to the defeat of the Philistines. King David led a series of military campaigns that made Israel a powerful kingdom, centering on Jerusalem, which he established as Israel’s capital. [3] He ruled around 1000 B.C.E. until he died in 970 B.C.E.

Source: James Tissot, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

King David’s son, King Solomon, took over the kingdom after his father’s death. The most widely accepted period of Solomon’s reign is between 970 and 931 B.C.E. During Solomon’s reign, he ordered the construction of the First Temple in Jerusalem – also known as Solomon’s Temple – which was completed in 957 B.C.E. The temple housed the Ark of the Covenant, which became the most sacred relic of the Israelites. The Ark, in turn, contained the two stone tablets of the Ten Commandments. It also held Aaron’s rod – the miraculous rod carried by Moses’s brother, Aaron – and a pot of manna.

Shortly after King Solomon died in 931 B.C.E., the kingdom was divided into two parts: the Kingdom of Israel in the north and the Kingdom of Judah in the south.[4]

Under the Assyrian, Babylonian, and Hellenistic empires

In 722 B.C.E., the Assyrians invaded and destroyed the northern Kingdom of Israel. Many tribes fled to Judah, while other members fled, were deported, or were taken captive to other lands, thus creating the “Lost Tribes of Israel.”

In the summer of 587 B.C.E., King Nebuchadnezzar II and his wards laid siege to Jerusalem, ultimately leading to the destruction of the city and the First Temple. The Babylonian invasion also led to the exile of Jews to Babylonia, marking the first significant Jewish Diaspora. Both the Hebrew Bible and cuneiform tablets written during Nebuchadnezzar’s time narrate the events of the invasion. After the Babylonians conquered Judah, many Jews were sent into slavery. Although Cyrus the Great, the Persian ruler who conquered Babylonia, allowed the Jews to return to their homeland, a part of the Jewish community willingly stayed behind in Babylonia.

In 333 B.C.E., the Macedonian ruler Alexander the Great conquered the Land of Israel along with Egypt and the entire Persia, commencing the Hellenistic (Greek) rule over the region. After Alexander’s death in 323 B.C.E., his generals, known as the Diadochi (“successors”), disputed his vast territories resulting in the division of the empire into two kingdoms – the Seleucid Empire and Ptolemaic Egypt.

The Land of Israel would change hands between the two Greek kingdoms five times. When the Seleucids defeated the Ptolemaic Egyptians in the Battle of Panium near Banias (located on the Golan Heights) in 200 B.C.E., the Land became part of the Seleucid Empire. Since then, the Seleucids were in solid control of the region, and their rule would remain until the Maccabean Revolt in 168 – 164 B.C.E. During the Hellenistic period, the first translation of the Hebrew Bible in Greek, the Septuagint or the Greek Old Testament, was made in the mid-3rd century B.C.E.

The Second Temple

According to the Hebrew Bible, the Second Temple was built in 516 B.C.E. to replace the First Temple. The Bible also claims that the temple was originally a modest structure built by the Jews who had returned from their exile in Babylonia. However, during Herod the Great’s reign, the Second Temple was completely renovated and refurbished. Reconstruction of the Second Temple took place around 20 B.C.E., turning the once-modest building into a big, imposing, and magnificent (and more recognizable) edifice. Herod also became known for his colossal buildings throughout Judea, the expansion of Temple Mount, and the fantastic palaces in Herodium and Masada, among other projects.

However, biblical literature often portrays Herod as an evil ruler who tried to seek out and kill the baby Jesus, whom he perceived as a potential threat to his rule. According to the Bible, he ordered the killing of all infants in hopes of killing the baby Jesus. However, most scholars are skeptical of these biblical claims and question whether they actually happened.

The Maccabean Revolt and the Hasmonean dynasty

Source: Peter Paul Rubens and workshop, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

During the 2nd century B.C.E., the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes attempted to Hellenize the Jews by eradicating Judaism and desecrating the Second Temple. This provoked the Maccabean revolt in 168 B.C.E., led by a Jewish priest named Judas Maccabeus. This three-year conflict with the Seleucids ended with a Jewish victory and the end of Greek rule. This successful uprising is told in the Books of the Maccabees in the Hebrew Bible.

Following the victory, Judas Maccabeus ordered the cleansing of the Temple. After the cleansing of the Temple and the installation of a new altar there, Judas Maccabeus and his troops held an eight-day festival at the Hanukkah (“dedication”) of the altar.

Two decades after Judas Maccabeus defeated the Seleucids, his brother Simon Thassi (Simon Maccabeus) established the Hasmonean dynasty in 140 B.C.E. and thus became its first ruler. The Hasmonean dynasty was largely a family affair consisting of priest-kings of Maccabean descendants. The last Hasmonean king, Antigonus II Mattathias (who reigned from 40 – 37 B.C.E.), was deposed and executed by the Romans under Mark Antony. The last member from the Hasmonean house, Mariamne I, was the second wife of Herod the Great, who put her to death for adultery. He also executed their two sons, Alexander and Aristobulus IV.

Under the Roman Empire

Source: Arthur Szyk, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

In 63 or 64 B.C.E., the Roman general Pompey the Great conquered Syria and played a significant part in the Hasmonean Civil War, which resulted in a decisive Roman victory. The Romans granted the Hasmonean king, John Hyrcanus II, limited authority under the Roman governor of Damascus. The Jews welcomed this new regime with hostility and would see frequent insurrections in the ensuing years.

The Herodian Dynasty

Source: Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Herod the Great, who also happened to be John Hyrcanus’s son-in-law, was appointed by the Romans as King of Judea in 37 B.C.E. He was noted for his massive construction programs across the region, including the renovation of the Second Temple (mentioned earlier in this article). He also founded the city of Caesarea on the Mediterranean coast. But despite his vast achievements, Herod failed to gain the trust and support of his Jewish subjects.

Herod died in 4 B.C.E. (or 1 B.C.E.). Ten years after his death, Judea directly became under Roman rule. The Romans’ increased persecution of the Jews incited sporadic violence that grew into full-scale rebellions that began in 66 C.E.

Jewish rebellion against the Romans

In 66 C.E., tensions between the Jews in Judea and the Roman rulers reached a crisis. The Jews instigated a revolt against the Romans and named their new state “Israel.” The rebellion culminated in 70 C.E. with the siege of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Second Temple. Jewish resistance continued, including the desperate last stand in Masada in 73 or 74 C.E. The events were described by ancient Jewish writer and historian Josephus (37 – c. 100 C.E.) who told the events from these rebellions. In one of his accounts, he wrote that the Masada’s defenders – called by today’s scholars the Zealots – chose to commit suicide rather than surrender to the Romans: “For the husbands tenderly embraced their wives, and took their children into their arms, and gave the longest parting kisses to them, with tears in their eyes.” [5]

In 131 C.E., the Roman emperor Hadrian turned Jerusalem into a pagan city called “Aelia Capitolina” and built the temple of Jupiter on the site of the destroyed Second Temple.

Further rebellions ensued over the decades, ultimately ending with the Bar Kokhba revolt (132 – 136 C.E.). The Jewish leader Simon Bar Kokhba led another major revolt against the Romans. The people looked up to Bar Kokhba as the “Jewish messiah” who would restore Israel to its former greatness. Initial rebel victories over the Romans enabled the Jews to establish an independent state over most of Judea for over three years.

But eventually, Emperor Hadrian and his wards crushed the revolt with unspeakable brutality. It culminated with the Fall of Betar on the 9th of Av (Tisha B’av), where Hadrian’s army besieged Betar, the last Jewish military stronghold. After a fierce and bloody battle, every Jew in Betar was killed (the Talmud describes the horrific scenes of this battle). The Romans also put the eight members of the Sanhedrin (the supreme religious body) to death in a series of brutal executions.

According to the ancient Roman writer and historian Cassius Dio (155 – 235 C.E.), the Bar Kokhba revolt resulted in the deaths of around 580,000 Jews; many more died of hunger and disease. The devastation of Jewish communities and the large-scale annihilation of the Judean population reached the extent that some scholars conclude it was a genocide.

Hadrian’s persecution of the Jewish people persisted until his death in 138 C.E. His successor, Antonius Pius, not only reverted some of Hadrian’s decrees but was also quite benevolent toward the Jews. However, the Jews’ spirit had already been crushed beyond recognition. The Bar Kokhba revolt effectively ended any Jewish hopes of autonomy in their homeland until the 20th century.

After the Jewish defeat

Following the suppression of the Bar Kokhba uprising, the Judean independence was lost as the Romans exiled most Jews from Judea. Furthermore, Hadrian banned the Jews from entering Jerusalem – then Aelia Capitolina – except on every 9th of Av to mourn their losses in the revolt. The Jews were also barred from entering the Judea province, which had been renamed “Syria Palestina” following the revolt.

However, the Romans didn’t send the Jews out of Galilee. Moreover, the Romans permitted a hereditary Rabbinical Patriarch, called “Nasi” (“Prince”), to represent the Jews in dealings with them. Probably the most famous “Nasi” is Judah ha-Nasi (135 – 217 C.E.) who is credited with completing the codification of the Mishnah, the Jewish oral law, in 210 C.E.

The Roman Empire, under the leadership of Constantine the Great, adopted Christianity as an accepted religion. Constantine, a Christian convert himself, moved the empire’s capital from Rome to Constantinople. He sent his mother Helena (Saint Helena) on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem; she is said to have been the first person to make a pilgrimage to the Holy Land.[6] He also supervised the construction of the Church of Nativity (traditionally, the birthplace of Jesus Christ), the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (the burial site of Jesus Christ) in Jerusalem (Old City), and other key churches that are still standing today. The Jews were still not allowed to live in Jerusalem but were permitted to make visits to the ruins of the Second Temple.

Tensions continued between Jews and Christians. It became a Christian policy to convert Jews into Christians, and Christian leaders used the official power in Rome in their conversion attempts. From 351 to 352 C.E., Jews in Galilee started another uprising, but this time against a corrupt Roman governor, Constantinus Gallus. However, the revolt resulted in a Roman victory, as well as thousands of rebels killed and the destruction of the major cities in Galilee. After the bloody conflict, a permanent garrison occupied Galilee.

The Byzantine period

Foreign domination continued in the Land of Israel, this time during the Byzantine period (320 – 636 C.E.). The transformation of Christianity from a reviled and outlawed religion into an official religion of the Roman Empire had a profound effect on the Jews and the pagans (gentiles) alike. In the centuries following Constantine’s conversion to Christianity in the 4th century, the ancestral polytheistic religions in Rome were outlawed. The great pagan temples were declared illegal – they were either desecrated or rededicated as Christian places of worship. Pagans and polytheists suffered brutal persecution.

In comparison, Jews fared better in this new Christian empire. Judaism was the only non-Christian religion that was tolerated, at least initially. Being an ancient and “legal” religion, Judaism was protected from Christian persecution and this “privilege” for the Jewish people was maintained from the fourth and fifth centuries.

But as the sixth and seventh centuries wore on, this protection was slowly replaced by new restrictions, which meant bad news for the Jews. Existing synagogues were either destroyed or rededicated as new Christian places of worship while the construction of new synagogues was banned. Jews were forbidden from holding public office or owning slaves. All these happened while the government did little or nothing to protect them.

Despite growing anti-Semitism, Jewish culture thrived during this period, at least in the Land of Israel. Synagogues continued to be built throughout the Jewish areas of Palestina, often with beautifully decorated mosaics and polished stone menorahs. The existing ruins of the synagogues built during this era show evidence of the Byzantine art influence. These mosaics have designs showing people, menorahs, animals, Biblical characters, and even zodiacs. Jewish literature also thrived during this period, although the age of the great Rabbinic scholars had gone and most rabbis at the time did their works in anonymity. The sacred Jewish texts written at the time included the Gemara, the Jerusalem Talmud, and the Passover Haggadah.

Continued foreign domination from the Middle Ages to the modern period

Early Muslim period

The Muslim rule over the Land of Israel began four years after the death of Muhammad in 632 and went on to last for over four centuries. In 636, an army led by caliph Muawiyah I conquered Palestine and the entire Levant (a former region comprising present-day Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, Palestine, and most of Turkey), making it a part of the Arab Empire. It marked the Arabian or Muslim period in the Land of Israel or Palestine. As a result, the ban on Jews during the Byzantine era was lifted and Palestine eventually became politically and socially dominated by Muslims, although the predominant religion may have remained Christian.

The Muslim conquest and rule over Palestine would last for over four centuries, with the caliphs ruling first from Damascus, and then from Baghdad and Egypt. In the beginning of the Arab rule, Jewish settlements in Jerusalem resumed. Jews living in an Islamic state at the time were given legal protection and thus were called “dhimmi”. The “dhimmi” status safeguarded the Jews’ lives, property, and freedom of worship, in return for payment of special poll and land taxes.

But like in the Byzantine empire, the protection for the Jews began to slip away in the early 8th century. The new laws greatly affected the Jews’ public conduct, as well as their legal status and freedom of practicing their own religion. Added, the imposition of heavy poll and land taxes compelled many Jews to move from rural areas to cities, where their situation barely improved. Worse, the growing social and economic discrimination forced other Jews to leave the country. Persecution among Jewish as well as Christian inhabitants by their Muslim leaders increased. By the end of the 11th century, the Jewish community in Islamic land significantly diminished. Along with the departure of the Jews from the Islamic land came their organizational and religious disintegration.

One of the most distinctive buildings from this period still standing today is the Dome of the Rock, known for its magnificent gold-plated roof. It was initially completed from 691 to 692 C.E. at the order of Umayyad Caliph Abd al-Malik. Currently located on Temple Mount in Jerusalem, this gilded Islamic shrine was built on the site of the Second Temple.

The Crusaders

The European forces of the First Crusade began a siege in Jerusalem. This siege, which lasted from June 7 to July 15, 1099, resulted in the capture of Jerusalem from the Muslim caliphate and, subsequently, the establishment of the Christian Kingdom of Jerusalem. The knights of the First Crusade massacred most non-Christians inhabiting the city. Some 6,000 Jews, who sought refuge in their synagogues, defended their quarter only to be burned to death or sold to slavery.

In the next few decades, the Crusaders spread their power over the rest of the Holy Land, partly through agreements and treaties, but mostly through bloody wars.

When the Crusaders opened transportation routes from Europe to the Holy Land, the number of pilgrimages increased. At the same time, the opening up of the Holy Land to foreigners became an opportunity for the Jews to return to their homeland. Extant documents from this period indicate that a group headed by 300 rabbis from France and England arrived in Palestine around 1211, further strengthening the local Jewish community there. Some of the group settled in Akko (Acre), others in Jerusalem.

The Crusaders’ rule fell in 1187 when Sultan Saladin and his troops defeated the knights and subsequently captured Jerusalem and most of Palestine. Once again, the Jews were granted a certain measure of freedom, including the right to return and live in Jerusalem. After Saladin’s death in 1193, the Crusaders regained their foothold in the country, although this time their presence was limited to a network of fortified castles.

The Siege of Acre in 1291 led to the Crusaders losing control of Acre to the Mamluks, marking the permanent end of the Crusaders’ rule in the Holy Land. The fall of the Crusaders was followed by increased persecution of the Jews in Europe, where they were expelled, murdered, or forced to convert to Christianity. Hundreds and thousands of Jews, particularly in Spain, were forced to convert to Roman Catholicism to avoid expulsion – or worse. They were called conversos — but these conversos were Catholics in name only as they still practiced Judaism in secrecy. Many covert Jews chose to settle in the New World, where they could practice their religion more freely.

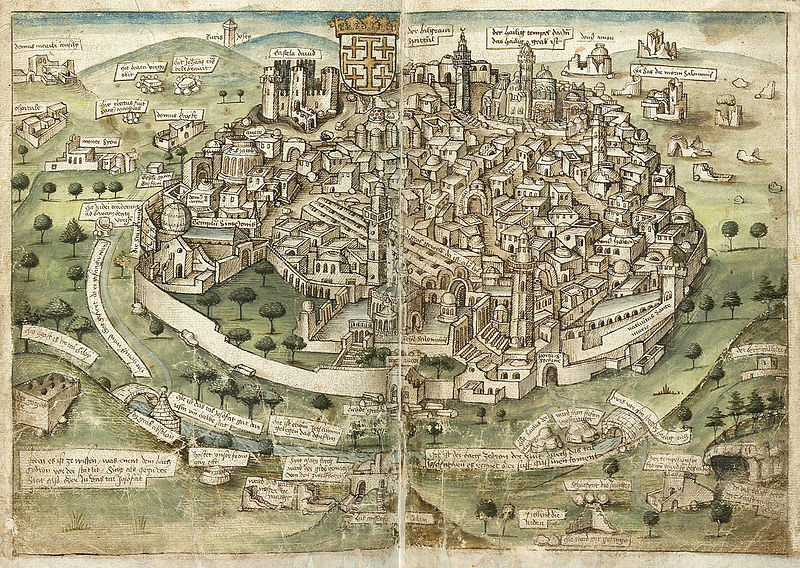

Source: Konrad Grünenberg, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Mamluks

The Mamluks (literally, “slaves”) were a military class that ruled Egypt (1250 – 1517) and Syria, including the Land of Israel or Palestine (1260 – 1516). Under the Mamluk sultanate, Jews often suffered discrimination and persecution at the hands of the Muslim leaders and zealots. At times, though, sultans from Egypt and Syria, as well as their representatives, did seek to restrain fanatical acts from Muslim mobs or leaders against non-Muslims.[7]

The Holy Land became a “backwater” province under Damascus. The ports in Acre, Jaffa, and other cities were destroyed for fear of another crusade in the offing. Maritime and overland commerce was also interrupted. The Jews’ situation in the Mamluk state began to decline in the second half of the 15th century. They were subject to discrimination and unjust obligation to pay taxes, even on simple pleasures like drinking wine. But it was the gradual economic decline of the sultanate, instead of anti-Jewish policies, that ultimately contributed to the dwindling of Jewish communities. The towns and cities were left virtually in ruins. Almost all of Jerusalem was abandoned and the small Jewish communities fell to abject poverty.

The Mamluk rule ended when the Ottomans gained control over Syria in 1516 and Egypt in 1517.

The Ottoman Empire

Israel, then known as Palestine, was conquered by Turkish Sultan Selim in 1516 to 1517, subsequently becoming a part of Ottoman Syria, along with much of the Middle East. Following the conquest, the Holy Land was divided into three states: Jerusalem, Gaza, and Nablus, all administratively attached to the Damascus Province.[8] The Ottoman Empire would rule over the Holy Land for the next 400 years.

At the beginning of the Ottoman rule, some 1,000 Jewish families lived in the region, mostly in Jerusalem, Gaza, Nablus (Shechem), Hebron, Safed (Tzfat), and several villages in Galilee.

Under the rule of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent until his death in 1566, the government brought improvements in and encouraged Jewish immigration. Apart from the descendants of the Jews who had never left the Holy Land since the failed revolt against the Romans, the growing Jewish community also consisted of immigrants from Europe and Africa. From around 1,000 people, the Jewish community grew to more than 10,000. Most Jews settled in Safed, which had become a thriving textile center as well as a hub for intellectual activity. Some of the newcomers, on the other hand, settled in Jerusalem.

During the Ottoman period, the study of Jewish mysticism, the Kabbalah, flourished. The Code of Jewish Law, Schulchan Aruch, completed in 1565, was also given contemporary clarifications that spread throughout the diaspora.

The Holy Land experienced a period of neglect during this period, but by the mid-19th century it saw signs of progress again, with various Western powers – coming mostly from the British, Americans, and French – jousting for position, mostly through missionary activities. Several Europeans and Americans opened their consulates in Jerusalem. The maritime activity saw signs of development again as steamships began to ply routes between Europe and the Holy Land. Postal and telegraphic communications were also introduced, and the construction of roads connecting Jerusalem to Jaffa also began. The Holy Land’s position as a junction for the commerce of the three continents was further bolstered by the opening of the Suez Canal.

With these changes and developments, the living conditions of the Jews gradually improved. Consequently, their number increased steadily. The Holy Land’s Yishuv community exponentially grew with aliyah – a term historically defined as the immigration of Jews from the Diaspora to Israel during its pre-state years, but now it refers to the immigration of Jews to the State of Israel. New rural settlements sprouted like mushrooms as land for farming could be purchased throughout the country. The Hebrew language, long restricted for liturgical and literary use, was revived and modernized for day-to-day communication. All these developments laid the foundations of the Zionist movement, which was also established as a response to the growing anti-Semitism both in the Holy Land and abroad. The first aliyah from 1881 to 1903 and the second aliyah from 1904 to 1914 further fueled the rise of Zionism and hopes for a Jewish homeland in the Ottoman-ruled Palestine.

Under the British Mandate

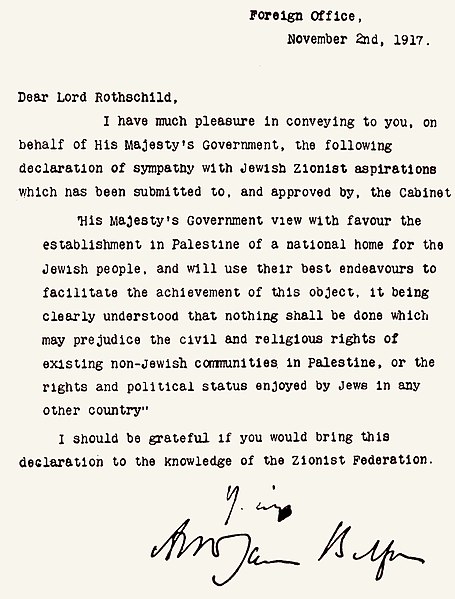

Source: United Kingdom Government signed by Arthur Balfour, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Ottoman Empire was a relatively calm period in the Land of Israel, then known as Palestine. But that calm would eventually be disrupted at the outbreak of World War I.

It was World War I that dramatically altered the geopolitical situation of the Middle East. During the height of the war, British foreign secretary Arthur Balfour sent a letter to Baron Rothschild – a banker, leader of the British Jewish community, and prominent Zionist – with the intention for the establishment of a Jewish “national home” in Palestine. The British government hoped that the formal declaration – which would be known as the Balfour Declaration – would help earn support for the Allies during the war.

The war ended with an Allied victory and the end of the Ottoman Empire’s rule. Great Britain took control over what was then known as Palestine, which consisted of present-day Israel, Palestine, and Jordan. The British mandate for Palestine was approved by the League of Nations in 1922, making the region a Mandatory Palestine. But the Arab Palestinians’ reaction to the mandate was less than welcome because it meant that the creation of a Jewish homeland would mean that their political and social rights might be endangered.

During the Mandate, a number of Jewish and Arab nationalist uprisings occurred, most notably the 1936 – 1939 Arab revolt and the Jewish revolt of 1944 – 1948. The Jewish insurgency led to victory for the Zionists and, ultimately, the withdrawal of the British from Palestine in 1948.

The U.N. partition plan for Palestine and the ensuing civil war

In 1947, the United Nations drafted a proposal for the partition of Palestine,[9] which was eventually adopted on the 29th of November. This proposal, known as Resolution 181, called for the creation of a Jewish state and an Arab state. The Jewish population, who actively lobbied for the plan, accepted it, inching closer to the realization of having a Jewish state. But the Arabs, understandably, rejected it, indicating an unwillingness to accept any kind of division in the land they lived in for several years.

Immediately after the U.N. Generation Assembly adopted the resolution, the Palestinian Arabs launched a civil war, with the ultimate intention of annihilating the Jewish state. As a result, the U.N. resolution failed to be implemented.

This civil war in Palestine, which lasted from November 1947 to May 1948, ended with a decisive Jewish victory. It also led to the expulsion of some 700,000 Palestinian Arabs from their homes and the migration of around 850,000 Jews (mostly coming from Muslim countries) to Palestine.

The State of Israel

Declaration of Israeli independence, and the 1948 Arab-Israeli War

Rudi Weissenstein, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

David Ben-Gurion, the head of Jewish Agency (the organization that accepted the U.N. partition plan) and the executive head of the World Zionist Organization, declared Israel as an independent state on May 14, 1948 before the British mandate expired. Ben-Gurion, known as the “founding father” of Israel, would be the state’s first Prime Minister.

But despite being a newly independent state, it didn’t end Israel’s troubles; rather, it was only their beginning. Only a day after Israel was declared an independent state, five Arab countries – Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria – immediately invaded the region, sparking the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. It would be the beginning of a years-long (and still-ongoing) Arab-Israeli conflict.

The Israelis, led by paramilitary groups such as the Haganah – the forerunner of the Israel Defense Forces (I.D.F.) – were severely outgunned and outmanned. They only had three tanks and didn’t even have warplanes. They were in extreme comparison to the well-equipped Arabs who had hundreds of tanks, warplanes, and field guns. But in the end, the Israelis successfully defeated their Arab enemies. In addition to retaining the territories allotted to them by the 1947 U.N. partition plan, the Israelis even managed to seize some 60% of territories originally allotted to the Arabs.

Israel was admitted as a member of the United Nations on May 11, 1949, almost a year after declaring its independence.

The Arab-Israeli conflict

Government Press Office (Israel), CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Since the first Arab-Israeli war of 1948, other conflicts and acts of violence between the Israelis and Arabs have followed for the next several years. These conflicts still occur up to the present. Here are some of them:

- The Suez Crisis (also known as the Second Arab-Israeli War, Tripartite Aggression, and the Sinai War) — Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser announced the nationalization of the foreign-owned Suez Canal,[10] the important shipping route connecting the Red Sea to the Mediterranean Sea. Israel, together with the United Kingdom and France, invaded Egypt with the objective of removing Nasser and regaining control of the Suez Canal in late 1956. Although Israel managed to occupy Sinai, it withdrew in March 1957 under pressure from the Americans and Soviet Russians. Even so, Israel ended up successful in some of its objectives, most notably attaining navigation rights to the Straits of Tiran, which Egypt had barred to Israeli shipping since 1950.

- Six-Day War – It was a war fought in June 1967 between Israel and the Arab states consisting of Egypt, Jordan, and Syria, with minor involvement from Lebanon and Iraq. This brief, week-long war ended with a decisive victory for the Israelis, who subsequently captured the Gaza Strip and the Sinai Peninsula from Egypt, East Jerusalem and the West Bank from Jordan, and the Golan Heights from Syria.

- War of Attrition – It was a limited war fought between Israel and Egypt, with minor involvement from Jordan, the Palestine Liberation Organization (P.L.O.), Syria, and the USSR, from July to August 1970. The Egyptians initiated the conflict as an attempt to reclaim Sinai from the Israelis, who had been in control of the territory since the June 1967 war. The conflict ended with a ceasefire; neither side won or lost, and the disputed territories remained in the same place as the war began.

- Yom Kippur War – It was a war fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab states, led by Egypt and Syria, in October 1973. The Arabs attempted to win back some of the territories which they lost to the Israelis after the June 1967 war. Egypt and Syria launched surprise joint attacks on the Israeli troops, most of whom were away from their posts in observance of Yom Kippur, the holiest day for the Jews. Eventually, the Israelis defeated the Arab forces (but at a high cost), with no significant territorial changes.

- Lebanon War – It was a war fought between Israel and Lebanon from June 1982 to June 1985. The I.D.F. invaded Lebanon and expelled the P.L.O. Israel’s attack on Lebanon was triggered by an assassination attempt on Israel’s ambassador to the UK, Shlomo Argov, by some members of a Palestinian nationalist militant group. In addition to the expulsion of the P.L.O. from Lebanon by the Israelis, the war resulted in the creation of an Israeli Security Zone in southern Lebanon.

- First Intifada – (from the Arabic word “intifada,” which means “uprising”) was a large-scale Palestinian uprising against the Israeli occupation of Gaza and the West Bank from 1987 to 1993. Casualties included hundreds of Israeli deaths and thousands of Palestinian deaths. The conflict resulted in the creation of a peace process, famously known as the Oslo Accords, and the establishment of the Palestinian Authority (which took over some territories from the Israelis). In 1997, Israeli troops withdrew from some parts of the West Bank.

- Second Intifada – It was the second Palestinian uprising against Israel that lasted from 2000 to 2005. The late former Prime Minister Ariel Sharon’s visit to the Temple Mount triggered the violence, which eventually ended with a high number of casualties among both Israelis and Palestinians. The conflict also resulted in the withdrawal of the Israeli forces from the Gaza Strip and the construction of the Israeli West Bank barrier.

- Second Lebanon War – It was a war fought between Israel and Hezbollah – a Shiite Islamist militant group in Lebanon – from July to August 2006. It began as a military operation in response to the abduction of two I.D.F. reserve soldiers by Hezbollah, but it later intensified to become a bigger conflict. After about two months, the war ended with an UN-brokered ceasefire.

- Wars with Hamas– Israel has been involved in several conflicts with Hamas, a Sunni-Islamic nationalist and militant group that assumed Palestinian power in 2006. Since their first significant conflict in 2008, Israel and Hamas have engaged in the ensuing hostilities in 2012, 2014, and 2021.

The two-state solution

In recent years, many countries have been pushing for a two-state solution between Israel and Palestine. But it’s highly unlikely, at least for the time being, that the Israelis and Palestinians would settle on borders, as these boundaries are still subject to endless dispute and negotiation. For example, Palestinians and Arabs insist on the pre-1967 borders, which the Israelis do not view as acceptable.

During his tenure as Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu voiced his support for the two-state solution, but felt mounting pressure to change his stance. He was also accused of encouraging the construction of Israeli settlements in Palestinian areas while endorsing his support for the two-state solution.

One of Israel’s closest and most enduring allies is the United States. During his visit to Israel in 2017, U.S. former President Donald Trump encouraged Netanyahu to accept peace agreements with the Palestinians. The following year, the U.S. relocated its embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, which the Palestinians viewed as a gesture of America’s recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital. It was subsequently met by Palestinian protests at the Gaza-Israel border, which were quashed by the Israeli forces, resulting in the deaths and injuries of dozens of protesters.

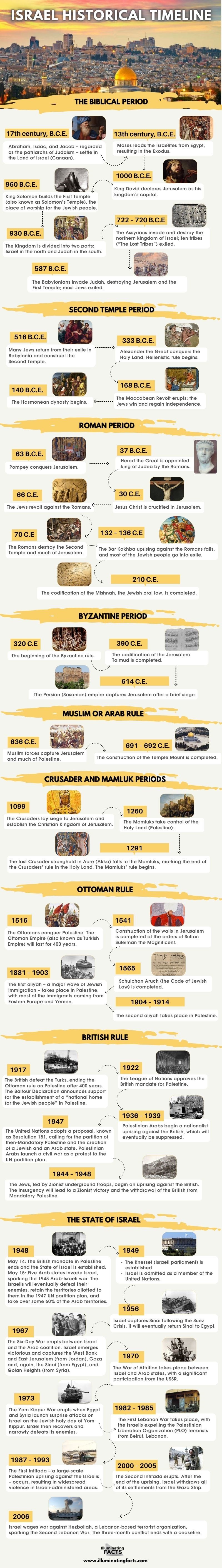

Overall timeline

This section deals with the most important and significant events of the State of Israel, from the biblical period to the present:

Immigration to Israel

Since the day the ancient Jews returned from their exile in Babylonia, Israel has been known as an “immigration nation.” Nine out of ten Israelis are immigrants or descendants of immigrants from the first and second aliyahs.

Israel was established as a homeland for the Jewish people and continues to be so up to this day. The past centuries of Jews in the Diaspora and several persecutions, from the age of antiquity up to the Holocaust or the Shoah (where around six million Jews perished), emphasize the importance of preserving Israel’s present and future status as the world’s only Jewish state.

The country’s unique “Law of Return” grants all Jews and people of Jewish descent the right to have Israeli citizenship. Since 1948, over three million people have immigrated to Israel.

Immigrants mostly come from Eastern Europe (including Ashkenazi Jews), while the rest come from Africa (mostly from Ethiopia), the Americas, and Asia (including the Arab or Muslim states).

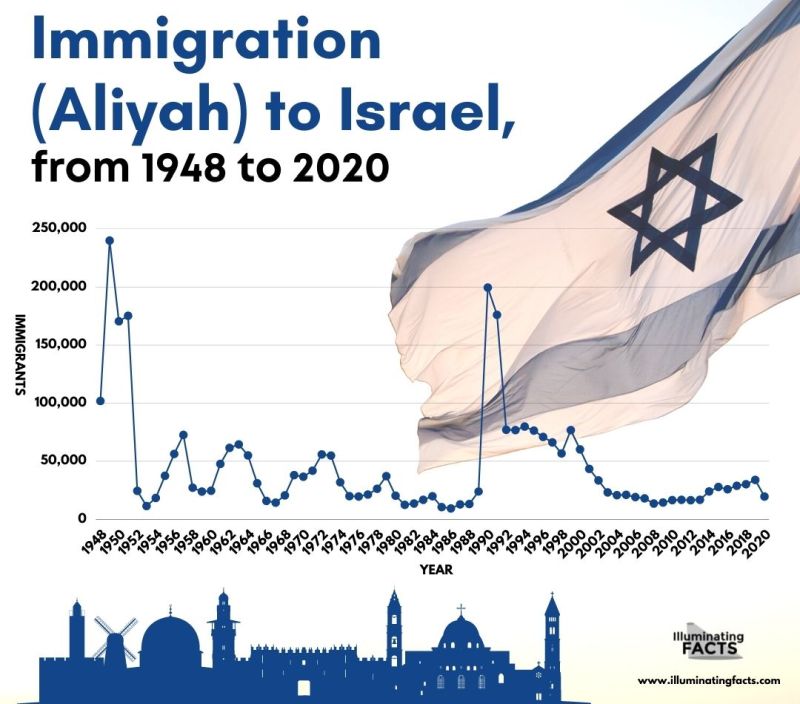

Below is the chart of Jewish immigration (aliyah) to Israel from 1948 to 2020:

Data source: “Total Immigration to Israel by Year.” Jewish Virtual Library. Available on: https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/total-immigration-to-israel-by-year

The years with the highest number of immigrations:

- 1949 – 239,954

- 1990 – 199,516

- 1991 – 176,100

- 1951 – 175,279

- 1950 – 170,563

Israeli settlements

There have been several Israeli settlements in the following disputed territories:

- West Bank (including East Jerusalem)

- Gaza Strip

- Golan Heights

- Sinai Peninsula

Israel captured all of these territories after the Six-Day War in 1967. Most of the Israeli settlers residing in these territories are Jewish.

Israel assumed full sovereignty to East Jerusalem in 1967 and the Golan Heights in 1981, claiming them as part of the country. However, observers from the international community have questioned the legitimacy of these unilateral annexations by Israel. Likewise, these annexations have also been disputed by the original inhabitants who still reside in these territories.

Since 2005, Jewish communities have increased steadily in the West Bank. As of July 2017, there were about 391,000 Israeli Jewish settlers (189,800 if East Jerusalem is excluded). In comparison, a few Israeli Jews have resided in the Golan Heights, somewhere around 20,000 to 22,300. But the international community claims that these settlements are regarded as illegal under international law, although Israel disputes this.

Israel dismantled or evacuated its settlements from the Sinai Peninsula and the Gaza Strip in 1982 and 2005, respectively.

There are a couple of big reasons for the existence of such settlements. One, the Israelis seek to recover the territories they lost (or weren’t able to capture) from the 1948 Arab-Israeli War and the hostilities leading up to it. Two – and this is the more practical reason – the Israelis have been motivated by cheaper housing and financial incentives offered by the Israeli government.

Below is the chart that shows the growth of the Israeli settlements from 1967 onwards:

Data source: “Total Population of Jewish Settlements.” Jewish Virtual Library. Available on: https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jewish-settlements-population-1970-present

As of November 2021, the number of Israel settlements has reached 457,481.

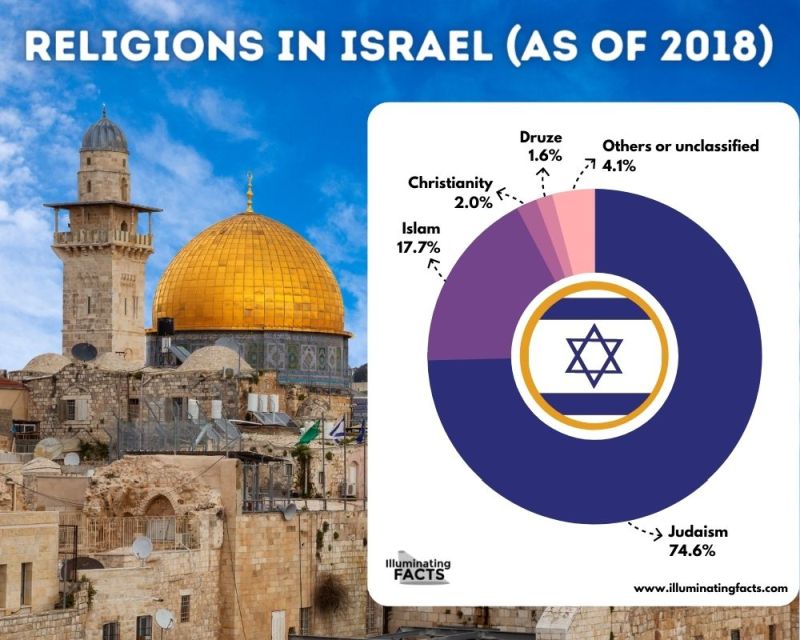

Religion

While Israel has no official religion, its definition as a “Jewish and democratic state” connotes its strong ties to Judaism, the ethnic religion of the Jewish people.

The Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 guarantees its citizens freedom and privilege to practice their own religion. By law and in practice, every religious community is free to exercise its faith, observe its holidays and days of rest, and conduct its own internal affairs.

Needless to say, religion plays a central role in the national and civic life of the Israelis. Every recognized religious community in Israel exercises control over several matters regarding personal status, especially marriage. While its predominant religion is Judaism, Israel has quite a diverse ethnoreligious landscape, thanks mostly to immigration. Among the other recognized religions in Israel include Islam, Christianity (all denominations), Druze, Baha’i, and other faiths.

Below is a chart of the religions practiced in Israel (as of 2018):

Data source: Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research

https://jerusaleminstitute.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/shnaton_C0918.pdf

Language

Israel has one official language, Hebrew. It is the only surviving member of the Canaanite language and by far the most successfully revitalized “dead language.” Hebrew survived into the Middle Ages but was only restricted to liturgy and literature.

But due to the rise of Zionism in the 19th century, Hebrew (Modern Hebrew, specifically) began to be used as an everyday spoken and written language. The use of Hebrew significantly increased among the Jews in the Diaspora and the Yishuv (Jewish residents in Israel during the pre-State era). About five million Israelis speak Hebrew as their native language.

Arabic used to be one of the official languages in Israel, but now it is classified as having a “special status” in the state since the adoption of the Basic Nation-State Law in 2018. Since the 2000s, the use of Arabic has increased, from road signs to food labels to official announcements. While Arabic-speaking Knesset members have the privilege to use the language, they rarely speak it during sessions. Besides, most of their Hebrew-speaking counterparts have no or little knowledge of Arabic.

Russian is, by far, the most widely spoken language in Israel that is neither official nor has a special status in the state. Some 20% of Israelis, most of whom are immigrants or descendants of immigrants from Soviet Russia, are fluent in Russian.

English, once widely used during the British Mandate era, gradually decreased during Israel’s early statehood. Initially, French was used as a diplomatic language in Israel and was also used in passports and other official documents alongside Hebrew. However, most state officials and civil servants still preferred to use English as they were more fluent in it than they were in French. But the faltering relations between Israel and France in the 1960s, along with Israel’s growing alliance with the United States, paved the way for English to regain its lost status. Despite Israel’s past history with the British, Israelis speak and write American English largely due to the recent American influence. Most Israelis understand, speak, and write English on at least a basic level. Road signs, public information signs, and plaques are also displayed in English, usually after Hebrew and Arabic. Several periodicals are also written in English. In fact, English is taught in public schools from elementary to high school. Most colleges and universities in Israel regard a high level of proficiency in English as a requirement for admission.

As Israel is a nation of immigrants, the country’s population has been linguistically diverse. Yiddish is a Germanic language with strong Hebrew elements. The primary language among Ashkenazi Jews, Yiddish has enjoyed a recent cultural revival in Israel after being banned during its early state years. Other large sectors in Israel speak Romanian, French, Polish, Spanish, German, Italian, Greek, Armenian, Amharic, etc.

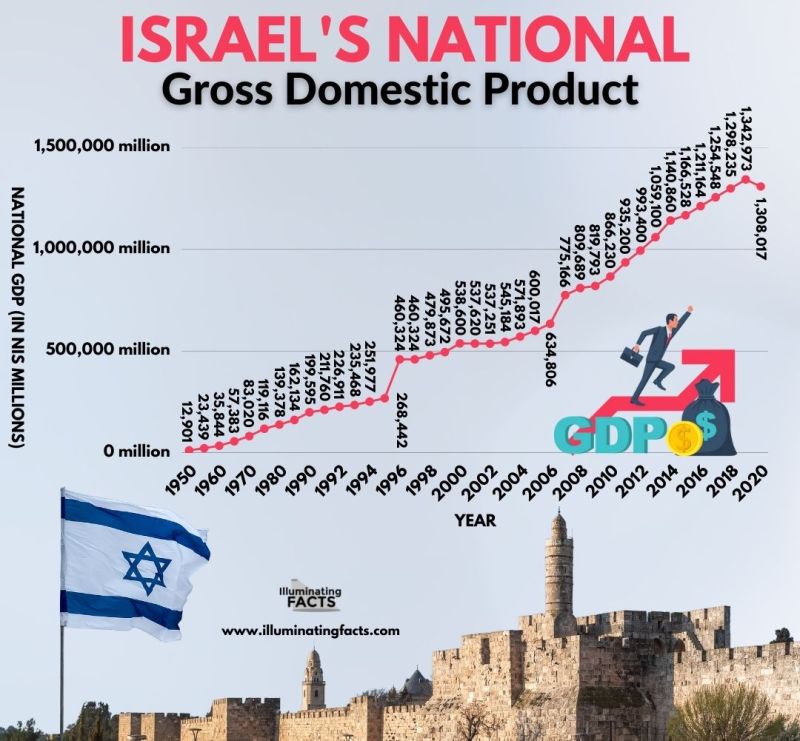

Economy of Israel

The Israeli economy is one of the world’s most resilient, vibrant, and technologically-advanced economies in the world. The country’s well-trained, highly educated, and entrepreneurial populace, along with the rapid establishment of universities and research centers, have contributed significantly to the rapid rise of its economy since the state’s founding.

Israel is one of the most economically and industrially developed countries in West Asia and the Middle East. Despite several odds, such as the scarcity of natural resources, a rapid population growth, tense relations with its neighbors, and a boycott by most Arab countries (most popularly the Palestinian-led B.D.S. – Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions), Israel has made significant strides in several fields and sectors. These sectors include agriculture, finance, energy, high technology, industrial manufacturing, and tourism.

The country has a well-developed science and technology sector. In fact, it spends a significant amount of its gross domestic product (G.D.P.) on research and development alone, which is among the highest in the world. As a result, Israel has 140 scientists and technicians per 10,000 people compared to only 85 per 10,000 in the United States.[11] It also has the highest number of start-ups, with one start-up per 1,400 people; among the globally famous start-up companies that started in Israel include Waze, Fiverr, Mobileye, and SodaStream. Thus, Israel ranks high in the number of scientists, technicians, and engineers, as well as the number of start-ups per capita, and venture capital investments per capita.

Due to its small consumer market domestically, Israel has expanded beyond its borders to sell its products and services and offer its technologies. Its recent inclusion as a member of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) is a clear indication of Israel’s status as one of the world’s economic powerhouses.

Tourism is also one of Israel’s major sources of income. With its plethora of religious and archaeological sites, beaches, natural sites, adventure sites, and ecotourism, Israel is a popular destination for both pilgrimages and regular holidays. In 2019 alone, the country posted 4.55 million tourist arrivals and in 2017 earned an added 20 billion shekels (US$6 billion) to its economy, making them an all-time record.

Below is a chart of Israel’s national G.D.P. from 1950 to 2020:

Data source: Israel Economic Indicators: National Gross Domestic Product (G.D.P.) (1950-Present) https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/israel-gross-domestice-product-gdp

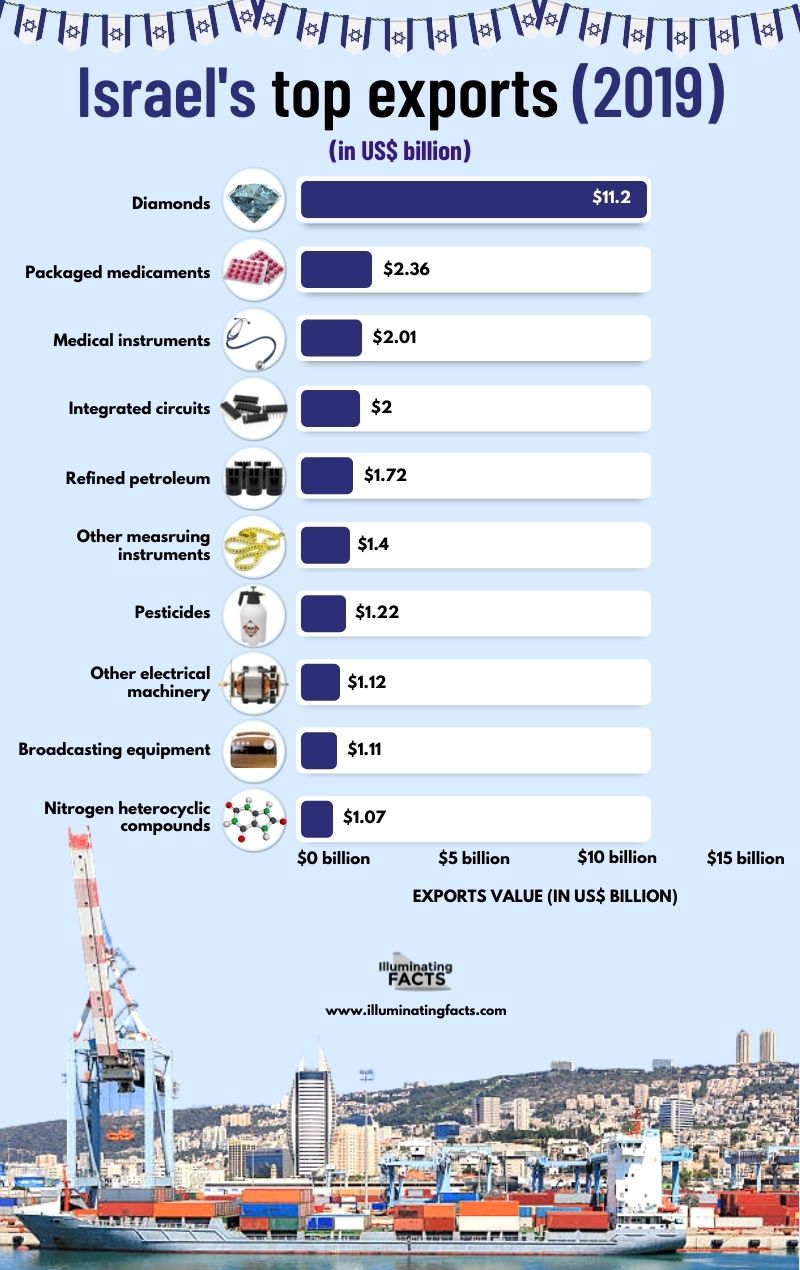

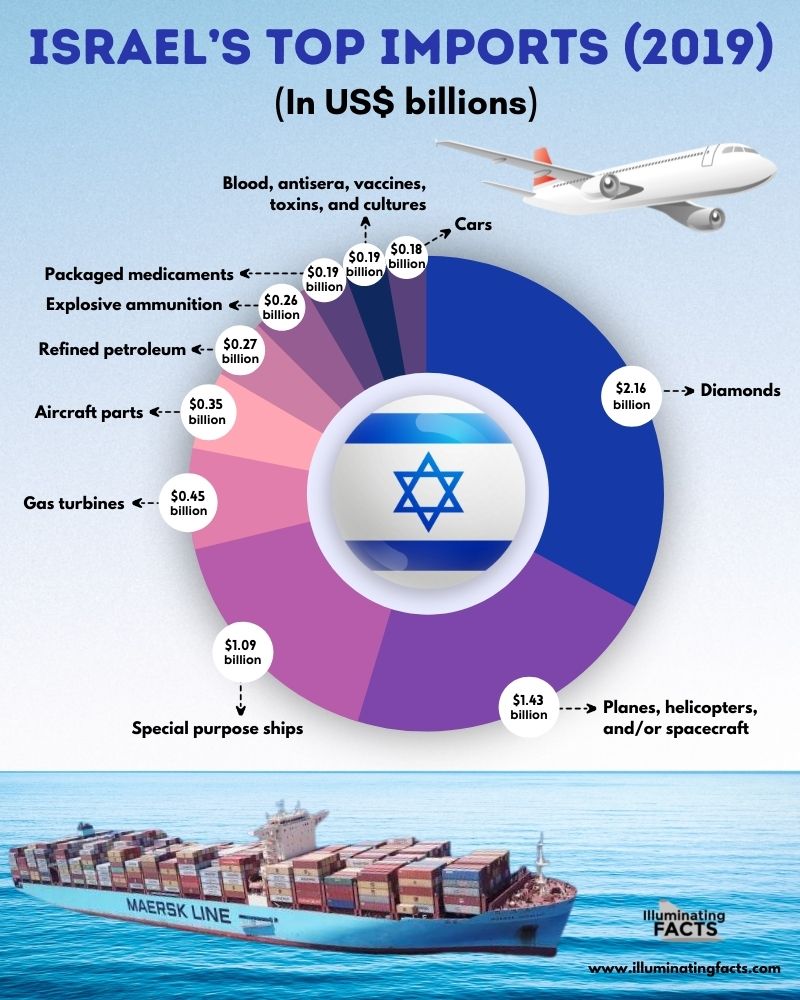

Trade

According to the Observatory of Economic Complexity (O.E.C.), Israel was ranked 50th in total exports and 43rd in total imports, as of 2019.

Among Israel’s main exports include cut diamonds, electronic components and other high-technology equipment, tools and machinery, refined petrochemicals, medical instruments, and packaged medicament. Imports, on the other hand, consist of raw materials, crude petroleum, refined petroleum, broadcasting equipment, and other finished consumer products. Its main trading partners are the United States, China, Germany, Hong Kong, Turkey, United Kingdom, the Netherlands, India, Switzerland, France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Japan.

Here are the top exports and imports of Israel, as well as its export destinations and import origins (as of 2019):

Data source: Observatory of Economic Complexity

https://oec.world/en/profile/country/isr

20 interesting and fun facts about Israel

1) Israel is home to the lowest point on earth – the Dead Sea (pictured), which is located 1,315 feet (400 meters) below sea level. The Dead Sea is one of the most popular tourist destinations in Israel, where people love to float on the dense and salty lake and lather themselves with mineral-rich mud.

2) Israel has the most museums per capita than any other country in the world, including the world’s only underwater museum (located in Caesarea).

3) Israel has the highest number of start-ups per capita, hence its moniker “The Start-Up Nation.” It is home to some well-known start-up companies, such as Waze, Fiverr, and SodaStream.

4) Israel is the only country to have successfully revived a dead language and made it its official and national language – Hebrew.

5) Israel has the world’s highest rate of university degrees on a per capita basis.

6) The 3,000-year-old Jewish cemetery in the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem (pictured) is the world’s oldest existing and continuously used cemetery.

7) Israel is one of the seven countries in the world that don’t have a codified constitution.

8) Where can you find the world’s only kosher glue used for postage stamps? Only in Israel!

9) Over one million notes are placed on the Western Wall (Kotel) in Jerusalem each year.

10) In Tel Aviv, there is an enclave called the “White City” where you can find a collection of over 4,000 Bauhaus buildings built in the 1930s. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

11) Not surprisingly, wine is pretty abundant in Israel, as winemaking has been around since biblical times. The country has 35 commercial wineries and around 250 boutique wineries. Galilee (including Upper and Lower Galilee and the sub-regions of the Golan Heights), the Judean Hills, the Samson region, the Negev desert region, and the Shomron region are among the most notable “wine countries” in Israel. Around 60,000 tons of wine grapes are harvested in Israel every year.

12) If you are a beach bum, you won’t feel short of the beautiful beaches in Israel as it has 137 of them.

13) There is no Starbucks in Israel. The American-based global coffee chain actually attempted to establish its presence in Israel by opening six stores, all in Tel Aviv. But after only two years, Starbucks folded in 2003. Forget political issues; it’s simply because local coffee shops serve better espressos and cappuccinos.

14) Israel has been at the forefront when it comes to the invention of new technologies. Some of the technologies Israel has produced include the cell phone, the USB flash drive, voice mail technology, the Pentium MMX chip technology, instant messaging, the first antivirus software, and the Windows NT operating system.

15) The Israel Defense Forces is among the few armies in the world with a mandatory conscription requirement for women.

16) Israel is the only liberal democracy in the Middle East where women also enjoy full human rights.

17) Israel has the most number of fruit and vegetable consumers per capita.

18) Israel is one of the world leaders in agriculture. It introduced drip irrigation and gave the world thornless prickly pears and the sweet variety of cherry tomatoes. It also produces 95% of its food for domestic consumption.

19) Israeli rabbis, with the help of scientists, rule that giraffe milk is kosher.

20) Despite being surrounded by a tough neighborhood, Israelis are rated as some of the happiest people in the Western world, according to several studies.

References

[1] AFP, 2019. “Benjamin Netanyahu says Israel is not a state of all its citizens.” The Guardian. Available on: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/mar/10/benjamin-netanyahu-says-israel-is-not-a-state-of-all-its-citizens [accessed November 12, 2021]

[2] Bibleref.com editors. “Genesis 32:29 Parallel Verses.” BibleRef. Available on: https://www.bibleref.com/Genesis/32/Genesis-32-29.html [accessed November 12, 2021]

[3] Owen Jarus, 2016. “Ancient Israel: A Brief History.” Live Science. Available on: https://www.livescience.com/55774-ancient-israel.html [accessed November 12, 2021]

[4] History.com editors, 2021. “Israel.” History.com. Available on: https://www.history.com/topics/middle-east/history-of-israel [accessed November 12, 2021]

[5] Owen Jarus, 2012. “Masada: Fortress of the Zealots.” Live Science. Available on: https://www.livescience.com/24796-masada.html [accessed November 12, 2021]

[6] David Hendin, 2016. “St. Helena, the first Christian pilgrim.” American Numismatic Society. Available on: http://numismatics.org/pocketchange/helena/ [accessed November 12, 2021]

[7] Eliyahu Astor and Reuven Amitai, 2008. “Mamluks.” Jewish Virtual Library. Available on: https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/mamluks [accessed November 12, 2021]

[8] Erhan Afyoncu, 2018. “400 years of peace: Palestine under Ottoman rule.” Daily Sabah. Available on:

https://www.dailysabah.com/feature/2018/05/18/400-years-of-peace-palestine-under-ottoman-rule [accessed November 12, 2021]

[9] Martin Kramer, 2017. “Why the 1947 U.N. Partition Resolution Must Be Celebrated.” The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Available on: https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/why-1947-un-partition-resolution-must-be-celebrated [accessed November 12, 2021]

[10] History.com editors, 2009, 2021. “Suez Crisis.” Available on: https://history.state.gov/milestones/1953-1960/suez [accessed November 12, 2021]

[11] Israel Inside Out (n.d.). “How Did Israel Become a Start-Up Nation?” Available on: https://israelinsideout.com/science-and-technology/how-did-israel-become-a-start-up-nation.html [accessed November 15, 2021]

.jpg)