Throughout history, dragons have independently appeared in the mythology, folklore, and artwork of numerous cultures and civilizations. [1]

The Latin ‘dracōnis’ and the Greek ‘drakōns’ are the origins of the word “dragon,” which first appeared in the English language in the 13th century. [1] Dragons appear in myth and folklore from all over the world, including Asia and Europe. They can be a minor annoyance or a deadly threat; they can fly and breathe fire or creep along spouting poison. They come in a variety of shapes and sizes. [2]

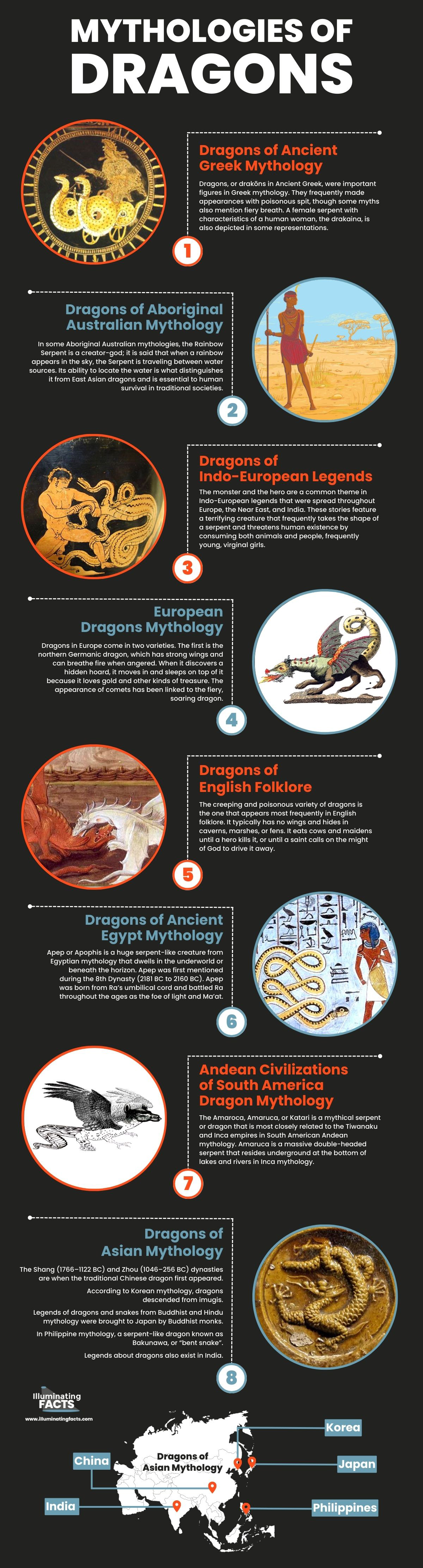

Mythologies of Dragons

1. Dragons of Ancient Greek Mythology

Dragons, or drakōns in Ancient Greek, were important figures in Greek mythology. They frequently made appearances with poisonous spit, though some myths also mention fiery breath. A female serpent with characteristics of a human woman, the drakaina, is also depicted in some representations. Many Greek heroes faced or interacted with draconic features. The Lernaean Hydra was slain by Heracles, a dragon guarding the Golden Fleece was drugged by Jason, Zeus fought the monster Typhon, and Cadmus fought the dragon of Ares. [1]

Romans did not create their own dragon (Latin: Dracōnis) traditions; instead, they mostly modified Greek mythology to suit their purposes. The Draco served as the cohort’s military standard during the second century AD following the Dacian Wars, whereas the eagle (Aquila) represented the legion. [1]

2. Dragons of Aboriginal Australian Mythology

In some Aboriginal Australian mythologies, the Rainbow Serpent is a creator-god; it is said that when a rainbow appears in the sky, the Serpent is traveling between water sources. Its ability to locate the water is what distinguishes it from East Asian dragons and is essential to human survival in traditional societies. Serpents are widely regarded as possessing special knowledge of the secrets that are concealed beneath the earth’s surface in the world’s major mythological cycles. They can wriggle through the smallest cracks and crevices, disappearing into shadowy caverns, then emerging elsewhere. Their propensity to shed their skins may represent the new information they have learned in the enigmatic depths below. [2]

3. Dragons of Indo-European Legends

The monster and the hero are a common theme in Indo-European legends that were spread throughout Europe, the Near East, and India. These stories feature a terrifying creature that frequently takes the shape of a serpent and threatens human existence by consuming both animals and people, frequently young, virginal girls. Economic, political, and population crises are brought on by this. The hero frequently requires supernatural assistance, such as a flying mount like Pegasus or a magic sword, or he has superhuman strength, like the Greek hero Herakles (Hercules in Roman myth), who fought the multiheaded Hydra in the Lerna marshes. [2]

The monster doesn’t always have draconian features, but it frequently resembles a serpent and may live in the sea, like the sea monster that Perseus used the Gorgon’s head to turn into stone when he saved Andromeda. Or, like the Python, which the god Apollo killed with his arrows, it might be hidden deep within a rocky chasm. [2]

This archetype represents the never-ending struggle between good and evil, but more specifically, such tales are frequently used to illustrate how various peoples were able to colonize new lands by overcoming formidable obstacles and ingeniously navigating natural dangers to establish permanent settlements. [2]

4. European Dragons Mythology

Dragons in Europe come in two varieties. The first is the northern Germanic dragon, which has strong wings and can breathe fire when angered. When it discovers a hidden hoard, it moves in and sleeps on top of it because it loves gold and other kinds of treasure. The appearance of comets has been linked to the fiery, soaring dragon. Although they were initially perceived as a sign of the fierce Viking attack on the monastery at Lindisfarne, the dragons that were reportedly seen flying over North Umbria in 793 (according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle) were most likely a comet of some sort. [2]

The Old English epic poem Beowulf, which was most likely written in the early 11th century but was composed in the 8th century, is one of the literary works from which the fire-drake is best known. This dragon settled in after discovering a cache of treasures stashed away in an old barrow. The angry monster destroyed Beowulf’s great hall and tormented his people when a slave broke into the cave and stole a goblet. [2]

Armed only with a unique iron shield, the elderly hero entered the battle alone, but the monster grabbed his neck in its poisonous jaws. Wiglaf, a relative of Beowulf, hastened to assist him, and the two of them killed the creature. Beowulf had a grand funeral before passing away from his wounds. Unceremoniously, the dragon was tossed over a sea cliff. [2]

5. Dragons of English Folklore

The creeping and poisonous variety of dragons is the one that appears most frequently in English folklore. It typically has no wings and hides in caverns, marshes, or fens. It eats cows and maidens until a hero kills it, or until a saint calls on the might of God to drive it away. There have been theories that these dragon tales may be related to the discovery of dinosaur fossils or bones, or that the dragons’ lairs were located close to ancient battlegrounds, which would account for the human remains that were plowed up in the spring. However, there doesn’t appear to be any direct link between dinosaur discoveries and regional dragon myths or between battle locations and such tales. Even if they forget who was involved, people often remember that battles took place, and they don’t frequently associate such discoveries with monstrous animals. [2]

6. Dragons of Ancient Egypt Mythology

Apep or Apophis is a huge serpent-like creature from Egyptian mythology that dwells in the underworld or beneath the horizon. Apep was first mentioned during the 8th Dynasty (2181 BC to 2160 BC). Apep was born from Ra’s umbilical cord and battled Ra throughout the ages as the foe of light and Ma’at. [1]

Another enormous serpent, Nehebkau, guards the Duat and assisted Ra in his conflict with Apep. Though initially regarded as a bad spirit, he later serves as a funerary god connected to the afterlife and one of Ma’at’s forty-two assessors. [1]

The ouroboros, an ancient symbol showing a serpent or dragon eating its tail, is depicted in The Enigmatic Book of the Netherworld, an ancient Egyptian funerary text discovered in Tutankhamun’s tomb. During the Roman era, the symbol continued to be used in Egypt and frequently appeared on magical talismans, occasionally in conjunction with other magical emblems. [1]

7. Andean Civilizations of South America Dragon Mythology

The Amaroca, Amaruca, or Katari is a mythical serpent or dragon that is most closely related to the Tiwanaku and Inca empires in South American Andean mythology. Amaruca is a massive double-headed serpent that resides underground at the bottom of lakes and rivers in Inca mythology. [1]

Numerous dragons are also depicted in the cultures of Native Americans. Murals painted on bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River depict the Piasa Bird, a draconic figure that may have been an older iconograph from the significant Mississippian culture city of Cahokia. This figure appears in the mythology of the Illini people. [1]

The Horned Serpent, which is connected to water, rain, lightning, and thunder, is one of the most prevalent types of native American dragons and a recurring figure among many indigenous tribes of the Southeast Woodlands and other tribal groups. [1]

8. Dragons of Asian Mythology

China

Dragons (Chinese: lóng) were thought to bring good fortune and were a traditional symbol of strong, auspicious forces in Asia, particularly China. Dragons frequently served as the mounts or companions of gods and demi-gods, and Chinese emperors would use a dragon symbol to convey their imperial power. The earliest depictions of dragons in zoomorphic form come from the Xinglongwa culture, which flourished between 6200 and 5400 BC. Between 4700 and 2900 BC, the Hongshan culture may have popularized the Chinese character for “dragon.” [1]

The Shang (1766–1122 BC) and Zhou (1046–256 BC) dynasties are when the traditional Chinese dragon first appeared. It later developed into the Yinglong, a winged dragon Chen Zheng claims is the source of the “image of the real dragon.” [1]

Korea

It is most likely true that the Chinese dragon influenced many Asian nations, as evidenced by the Korean dragons’ longer beards and occasional depictions of them carrying the enormous orb known as the yeouiju. According to Korean mythology, dragons descended from imugis, serpent-like proto-dragons that aspired to become real dragons by capturing a Yeouiju that had fallen from heaven. [1]

Japan

Chinese dragons play a significant role in Japanese dragon legends, which even incorporate Chinese loanwords into the names of the creatures. The legends of dragons and snakes from Buddhist and Hindu mythology are thought to have been brought to Japan by Buddhist monks from other parts of Asia, though there are some instances of native dragons that are mentioned in ancient texts like the Kojiki and Nihongi. [1]

Philippines

In Philippine mythology, a serpent-like dragon known as Bakunawa, or “bent snake,” is thought to be responsible for eclipses, earthquakes, rain, and wind. Due to its syncretism with the Hindu-Buddhist serpent god Nga, Bakunawa is also sometimes referred to as Naga. It was also combined with Rahu and Ketu, the Hindu and Buddhist navagrahas who oversaw the eclipses of the sun and moon, respectively. [1]

With legends of Láwû, a serpent from Kapampangan mythology, Olimaw, a winged dragon-serpent from Ilokano mythology, and Sawa, a serpent monster from Tagalog and Ati mythologies, many Philippine serpents were linked to swallowing the moon. [1]

India

Legends about dragons also exist in India. The Vedic storm god Indra would engage in battle with a gigantic serpent known as Vrtra, according to the Rigveda, an ancient Indian collection of Vedic Sanskrit hymns. [1]

Where Did Dragons Come From?

According to experts, the belief in dragons likely developed independently in both Europe and China, as well as possibly in the Americas and Australia. How is this even possible? How the first legends were influenced by actual animals has been the subject of much speculation. Here is our list of the most likely candidates. [3]

1. Dinosaurs

It’s possible that ancient people found dinosaur fossils and understandably thought they were dragon remains. Such a fossil was misidentified by Chang Qu, a Chinese historian from the fourth century B.C., in what is now Sichuan Province. Look at a fossilized stegosaurus, for instance, and you might understand why: The enormous dinosaurs, which were typically 14 feet tall and measured an average of 30 feet long, were covered in spikes and armored plates for protection. [3]

2. Nile Crocodile

Nile crocodiles, which are native to sub-Saharan Africa, may have once had a larger range. By swimming across the Mediterranean to Italy or Greece, they may have given rise to European dragon legends. With mature individuals growing to a maximum length of 18 feet, they are one of the largest crocodile species. Unlike most others, they are also able to perform a movement known as the “high walk,” in which the trunk is raised off the ground. A huge, lumbering crocodile? It could be simple to misidentify it as a dragon. [3]

3. Goanna

Several species of monitor lizards, also known as goannas, can be found in Australia. Large, ferocious creatures with razor-sharp teeth and claws play significant roles in traditional Aboriginal folklore. According to recent studies, goannas may even produce venom that causes bite wounds to become infected after an attack. These creatures may be to blame for the dragon myth, at least in Australia. [3]

4. Whales

Others contend that tales of dragons originated as a result of the discovery of megafauna like whales. Ancient people who came across whale bones would not have known that the animals lived in the sea, and the thought of such enormous creatures might have led people to believe that whales were predatory. Live whales spend up to 90% of their time underwater, so for the majority of human history, little was known about them. [3]

5. Human Brain

The most intriguing explanation involves a surprising animal: a person. Anthropologist David E. Jones makes the case in his book An Instinct for Dragons that the reason why dragon mythology is so pervasive among ancient cultures is that human beings have an innate fear of predators thanks to evolution. Jones proposes that the trait of fearing large predators—such as pythons, birds of prey, and elephants—has been selected for in hominids, just as monkeys have been shown to exhibit a fear of snakes and big cats. He contends that these enduring fears were frequently combined in folklore in more recent times to produce the dragon myth. [3]

Interesting & Mystical Dragon Facts

- Dragons have existed for countless years. For countless years, they have been a part of mythology and culture around the world. They’re a part of some creation myths, too. People tell stories to help them comprehend how the world came to be. For instance, the creator goddess Tiamat is pictured as a dragon in ancient Mesopotamian art.

- Although dragons are present in all cultures, they are most prevalent in South Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. Dragon mythology has a long history in Japan as well, and the Vikings had Yggdrasil, a massive tree guarded by a dragon. While dragons are frequently featured in fairy tales and religious stories in Europe, they are also a significant part of the mythologies of India, Vietnam, and Korea. Dragons were feared in ancient Iraq because they could swallow men whole.

- The appearance of dragons varies. Asian and European dragons have very different appearances. Asian dragons typically lack wings and resemble long, snake-like creatures. They frequently carry their pearl-shaped egg in one claw. European dragons, on the other hand, have large, wide bodies, enormous scaly wings, and the capacity to breathe fire. They resemble lizards much more than snakes. They are pictured in the Bible as having numerous heads, somewhat like a Greek hydra. They could range in size from enormous, terrifying creatures the size of a cathedral to smaller, yappy dragons that are more akin to a large dog.

- Depending on their location, dragons can represent a variety of different things. They represent fortune, strength, and wealth in China. Dragons were frequently depicted on flags in Britain because killing one indicated that you were a formidable warrior. In Western culture, they frequently represent evil, and the devil is occasionally portrayed as either having dragon wings or being a dragon.

- Dragons are treasure hunters if you know anything about them. They are insatiable for it! This appears to have come from stories in ancient Greek literature about dragons protecting treasure from theft.

- There are statues and paintings of St. George fighting dragons all over Europe, making him the most well-known saint to have done so. He wasn’t the only saint to battle one, though. Margaret of Antioch battled a dragon as well, and when it tried to eat her, she had to fight her way free! Yuck! It wasn’t just her either. St. Theodore of Amasea, St. Philip the Apostle, and the archangel Michael are other saints who battled dragons.

- The world is full of dragon-themed artwork, memorabilia, statues, and murals. There are dragon gargoyles and statues, frequently depicting St. George slaying them, all over Europe. When you travel to countries like China, it’s common to see statues, pictures, and of course puppets of dragons because they are considered a symbol of strength and good fortune in East Asia.

- There aren’t any fire-breathing dragons in the real world. But we do have the Komodo dragon, which is the closest thing. Giant lizards called Komodo dragons can reach lengths of over 2.5 meters! They are members of the monitor lizard family and spend the majority of their time on the island of Komodo in Indonesia’s forests. When they first came across them, Western travelers probably truly believed they were seeing a dragon. Despite the fact that they do not breathe fire, they do have a very poisonous bite, so avoid them.

- In the past, people believed dinosaurs to be dragons. The first time fossilized dinosaur remains were found, people must have thought they had discovered something extraordinary. Initially believed to be dragon skeletons, these enormous lizard skeletons date back millions of years. They resemble a western dragon in many ways, but sadly none of them had matching large scaly wings. Dinosaurs that could fly had feathers instead.

- The dragon is Wales’ national emblem. This dragon may be familiar to you from the Welsh flag! Yes, the dragon is Wales’ national animal, and you can frequently see red dragons on items that are meant to symbolize Wales. Dragons are the subject of many myths and legends in Wales; the red dragon is thought to have been King Arthur’s emblem, while the golden dragon was the favorite of the Welsh prince Owain Glyndwr. The Tudors, who were originally from Wales, occasionally also used a dragon as their symbol.

References:

[1] Milligan, M. (2022b, August 27). The origins of dragon mythology. HeritageDaily – Archaeology News. https://www.heritagedaily.com/2022/08/the-origins-of-dragons/144532

[2] English Heritage. (n.d.). Dragons and their Origins. https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/inspire-me/blog/articles/dragons-and-their-origins/

[3] Stromberg, J. (2012, January 23). Where Did Dragons Come From? Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/where-did-dragons-come-from-23969126/